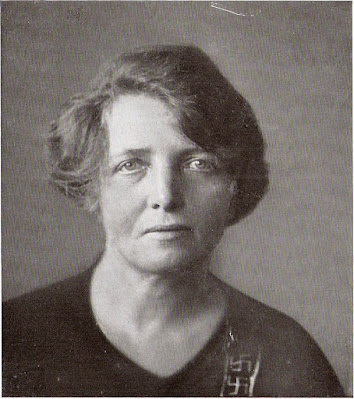

Ethical Pluralism (a new Mathilde Ludendorff) in relation to Kantian noumena

Comparison of Ethical Pluralism to Kantian Noumena: Similarities, Divergences, and Philosophical ImplicationsEthical Pluralism, as a reconstructed philosophy emphasizing irreducible plural essences, invites direct comparison to Immanuel Kant's distinction between phenomena (the world as it appears to us) and noumena (things-in-themselves, independent of our perception). Kant's framework, primarily articulated in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787), revolutionized metaphysics by limiting knowledge to the empirical realm while positing an unknowable reality beyond it. Ethical Pluralism echoes this bifurcation through its separation of "visible essences" (inside spacetime, akin to phenomena) and "invisible essences" (outside spacetime, akin to noumena), but it diverges in key ways: Pluralism rejects Kant's singular "thing-in-itself" for absolute multiplicity, integrates scientific pluralism (e.g., quantum indeterminacy), and emphasizes experiential access over absolute unknowability. This comparison reveals Ethical Pluralism as a post-Kantian evolution—preserving the critique of reason's limits while expanding into a dynamic, participatory ontology that bridges metaphysics, science, and ethics. Below, I explore this in depth, starting with Kant's concepts, then mapping Pluralism's parallels, highlighting differences, and concluding with broader implications.Kant's Phenomena-Noumena Distinction: A Foundational OverviewKant's critical philosophy arises from his "Copernican revolution" in epistemology: Rather than assuming our knowledge conforms to objects, objects conform to our modes of knowing. He argues that space, time, and causality are not objective features of the world but a priori forms of human sensibility and understanding—structures imposed by the mind to organize sensory data into coherent experience.

- Phenomena (Appearances): These constitute the empirical world we perceive and know. Phenomena are the "inside spacetime" realm: Objects as filtered through our cognitive faculties. For Kant, all scientific knowledge (e.g., physics, biology) pertains to phenomena, governed by categories like causality (every event has a cause) and spatial-temporal relations (e.g., succession in time). This realm is deterministic, measurable, and intersubjective—shared among rational beings. However, it is not "reality itself" but a constructed representation. Evolution, for instance, would be a phenomenal process: Observable adaptations in space-time, explainable causally via natural selection.

- Noumena (Things-in-Themselves): Noumena are the "outside spacetime" domain—the underlying reality independent of our perceptual filters. They are supersensible, existing beyond space, time, and causality, hence unknowable through theoretical reason. Kant posits noumena as a "limiting concept": We infer their existence to avoid solipsism (the world as mere illusion) but cannot positively describe them. They resolve antinomies (e.g., freedom vs. determinism): In phenomena, all is causally determined; in noumena, free will (moral agency) is possible. Noumena underpin ethics—Kant's categorical imperative operates in this realm, where pure reason accesses moral law without empirical contamination.

- Visible Essences as Phenomena: Pluralism's "inside spacetime" aligns with Kant's phenomena—conditional, finite realms governed by space, time, and causality. Essences like persistence (unicellular replication), finitude (multicellular death), and transformation (evolutionary adaptation) are empirical: Observable via science, structured by perceptual forms. For example, evolutionary biology describes phenomenal processes—branching phylogenies in temporal sequences—without accessing underlying "wills." Quantum mechanics' classical limit (deterministic at macro scales) echoes Kant's categories: Space-time as organizing principles for experience, not inherent properties.

- Invisible Essences as Noumena: Pluralism's "outside spacetime" parallels noumena—super-causal, atemporal/aspatial realms inaccessible to theoretical reason. Essences like transcendence (timeless contemplation), aspiration (purpose-free strivings), and relational fulfillment (discerned bonds) are "things-in-themselves": Experiential depths beyond empirical measurement. "God-Cognisance"—awareness of plurality—mirrors Kant's practical reason: Not theoretical knowledge but participatory insight, enabling moral agency. Myths (e.g., paradise lost) symbolize noumenal intuitions, purified in Pluralism as essences without literal heavens.

- Limits of Reason: Both critique reason's overreach—Kant via antinomies (e.g., infinite/finite universe); Pluralism via category errors (imposing unity on multiplicity). Reason suits visible essences (science) but fails invisible ones (metaphysics).

- Experiential Access: Kant allows noumenal influence via morality (free will); Pluralism via "God-living"—transcendent states where essences are apprehended experientially, not rationally.

- Ethical Grounding: Noumena enable Kant's deontology (duty beyond phenomena); invisible essences ground Pluralism's intrinsic ethics—affirmation of plurality without utility.

- Anti-Dogmatism: Both reject speculative metaphysics—Kant denies noumenal knowledge; Pluralism affirms essences' independence, avoiding personal gods or unified "wills."

- Singular vs. Plural Ontology: Kant's noumena are a singular, undifferentiated "x"—an unknowable substrate underlying phenomena. Pluralism rejects this: Invisible essences are multiple and irreducible (e.g., transcendence ≠ aspiration), without common aspect. This avoids Kant's "problematic" vagueness—essences like moral discernment are experientially distinct, not a homogeneous "beyond." Quantum multiplicity (superpositions without unity) supports this over Kant's Newtonian-inspired causality.

- Unknowability vs. Experiential Access: Kant deems noumena absolutely unknowable—theoretically inaccessible, practically inferred (e.g., via moral postulates). Pluralism allows participatory apprehension: "God-Cognisance" as direct experience of essences (e.g., timeless transcendence in contemplation), not inference. This builds on Kant's practical reason but extends it—science (visible) informs ethics, but transcendence enables super-rational insight, harmonizing with quantum non-computability (e.g., Orchestrated Objective Reduction in consciousness).

- Dualism vs. Absolute Separation: Kant's is a soft dualism—phenomena/noumena as aspects of one reality, with noumena "affecting" phenomena (via sensibility). Pluralism's absolute plurality eschews even this: Essences are ontologically separate, interacting contingently without "affecting" bridges—e.g., survival (inside) harmonizes with transcendence (outside) in "spiritualized" relations, but without causal linkage. Evolutionary contingency (no teleology) reinforces this over Kant's a priori categories.

- Static Limits vs. Dynamic Navigation: Kant fixes reason's bounds statically—noumena as eternal barrier. Pluralism views them dynamically: Consciousness navigates plurality, with moral discernment enabling ethical alignment across inside/outside. Science evolves (e.g., QM challenging classical causality), refining cognisance without violating limits.

- Deontology vs. Intrinsic Affirmation: Kant's ethics is duty-based (categorical imperative), noumenally grounded in freedom. Pluralism's is affirmative—intrinsically affirm essences (e.g., relational bonds), without imperatives; discernment guides, but fulfillment is experiential, not obligatory. This integrates Kant's autonomy but pluralizes it—no universal law, but contextual harmony.

- Ethical: Like Kant, it grounds morality beyond phenomena (aspirational essences as noumenal-like), but plural discernment enables flexible fulfillment, avoiding rigid duties.

- Religious: Myths parallel noumenal intuitions (e.g., eternity as atemporal essence), but Pluralism purifies into cognisance, rejecting personal gods for plural awareness.

- Scientific: Extends Kant's empirical focus—visible essences as phenomena, invisible as noumena—but integrates QM/evolution's multiplicities, defending pluralism against reductionism.

Comments

Post a Comment