Why did Mathilde Ludendorff reject Hinduism?

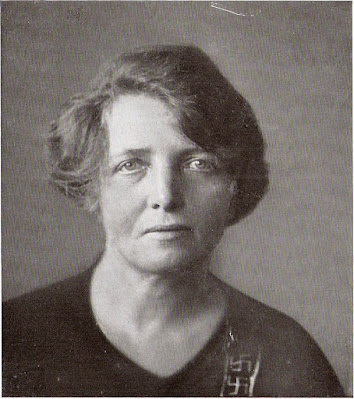

Mathilde Ludendorff's Rejection of Hinduism: A Focus on the Concept of Maya Mathilde Ludendorff (1877–1966), a German philosopher, physician, and nationalist thinker, developed a unique worldview in her seminal work *Triumph of the Immortal Will* (originally published in 1925 as *Triumph des Unsterblichkeitswillens*). Rooted in evolutionary biology, racial theory, and a rejection of traditional religions, her philosophy posits a "God-cognisance" (Gotterkenntnis)—a conscious, experiential union with the divine—that harmonizes scientific knowledge with an innate "Immortal-Will" (Unsterblichkeitswille). This Will, she argues, drives life's evolution from unconscious unicellular beings to human consciousness, where perfection is achievable through self-creation aligned with divine wishes: goodness, beauty, truth, and discriminated love/hate. Ludendorff's system emphatically rejects alien religions imposed on Nordic/Aryan peoples, viewing them as degenerative forces that disrupt racial purity and soul-laws. Among these rejected faiths, Hinduism holds a complex position in Ludendorff's critique. She acknowledges its ancient wisdom, particularly in recognizing the unity of all life and the limits of human perception, as seen in the Rig-Veda. However, she ultimately dismisses it as outdated, superstitious, and incompatible with modern scientific cognition. Central to her rejection is Hinduism's core concept of Maya—the illusion of the phenomenal world—which she sees as a profound error that stifles empirical inquiry, disdains the visible realm, and perpetuates a passive, fear-driven worldview antithetical to Nordic vitality and God-living. This essay explores Ludendorff's rejection of Hinduism, focusing on her critique of Maya, while contextualizing it within her broader philosophical framework. ### Ludendorff's Philosophical Foundation and the Place of Hinduism To understand Ludendorff's dismissal of Hinduism, one must first grasp her evolutionary theology. She traces human consciousness from primitive unicells, which possess "potential immortality" through endless division, to multicellular beings doomed to death but evolving toward higher awareness. Death, she contends, is not punishment for sin (as in many religions) but a necessity for birth and progress, enabling the Immortal-Will's spiritual fulfillment in God-cognisance before physical demise. This requires harmony between faith and knowledge: religions must align with scientific truths like Copernican cosmology, Darwinian evolution (reinterpreted without materialism), and Kantian philosophy, which distinguishes the phenomenal (visible, causal) world from the noumenal "Thing Itself" (Ding an sich)—the divine essence. Ludendorff praises pre-Christian Nordic/Aryan traditions for their "sidereal cult," focused on cosmic laws (e.g., seasons, stars) without priestly tyranny or fear of death. These fostered moral/cultural vitality through myths attuned to blood-inheritance and empirical observation. In contrast, she views Hinduism—exemplified by the doctrines of Jishnu Krishna (c. 6000 BCE, per her chronology)—as a relic of primitive intellect. While harmonious with ancient knowledge (e.g., recognizing life's unity: "What can be seen here to be different" from Rig-Veda), it predates modern discoveries, rendering it superstitious. Hinduism's derivations influenced Christianity (e.g., Krishna legends historicized as Jesus), which she calls a "folk-fraud" by Jews, blending hatred with illusionary myths. Hinduism's fatal flaw, for Ludendorff, lies in its metaphysical core: the denial of the visible world's reality via Maya, which perpetuates error and hinders the racial/spiritual harmony essential to her God-cognisance. ### The Concept of Maya: Definition and Ludendorff's Core Rejection In Hindu philosophy, particularly Advaita Vedanta and the Upanishads, Maya denotes the illusory nature of the phenomenal world. Derived from "ma" (not) and "ya" (that), it posits that the universe of appearances—time, space, causality, and multiplicity—is a deceptive veil obscuring Brahman, the ultimate, unchanging reality. The Rig-Veda's creation hymn (e.g., Jaitareya Upanishad) hints at this: After creation, the spirit discerns unity amid diversity but views the visible as mere deception. Maya is not non-existence but a superimposition (adhyasa) on the real, like a rope mistaken for a snake. Liberation (moksha) requires transcending Maya through knowledge (jnana), realizing the self (Atman) as Brahman. Ludendorff rejects Maya vehemently, viewing it as a primitive, fear-based misconception that disdains the visible world, blocking scientific progress and racial vitality. For her, Hinduism's Maya doctrine stems from early non-knowledge of nature's laws, where death/sorrow were misinterpreted as punishment or error, leading to cults of atonement. Indians, spared "Jewish" pollution, recognized uniformity ("all nature was one and the same") but feared phenomena as illusion, barring research into the visible (Erscheinungswelt). This "disdaining and fearing" Maya prevented knowledge yieldable only through empirical study, contrasting Nordic ancestors' cosmic sagas embracing seasons/stars for moral/cultural spirit. Ludendorff argues Maya reflects a warped intellect: Indians apprehended the invisible "Self" (Atman/Brahman) but deemed appearances deceptive, fostering passivity. Kant's noumenal "Thing Itself" echoes this but sharpens discernment between phenomenal (causal) and noumenal (supracausal). Nordics, pursuing nature's laws despite Christian persecution, achieved intellectual limits (e.g., Copernicus, evolution), harmonizing faith/knowledge. Hinduism's Maya, outdated post-Kant/Schopenhauer, intoxicates with illusion, irreverent to visible reality as divine manifestation. ### Broader Reasons for Rejecting Hinduism: Racial, Cultural, and Theological Incompatibilities Ludendorff's Maya critique ties into broader rejections of Hinduism as alien to Nordic blood. She sees it as primitive fetishism-analogous, limited to pre-scientific intellect, deriving Christian creeds (e.g., revelation/absurdity as holy) but polluted by Jewish "folk-fraud." Hinduism's fear-origin (death/spirits as punishment) birthed superstitions like reincarnation (changes for atonement), contrasting Aryan avoidance of hell/priests, focusing cosmic reliability for gratitude/union with God. Racial decay underpins her view: Hinduism's decline-era doctrines (Maya, asceticism) promoted indiscriminate love/forgiveness, ignoring race-purity/soul-laws, fostering degeneration. Nordics transformed alien Christianity via art (Gothic cathedrals as "hallowed groves"), but Hinduism's illusion-disdain stifled inquiry, unlike Nordic empiricism yielding science/God-cognisance. Theologically, Hinduism's personal gods/afterlife myths oppose her impersonal, experiential God-living pre-death. Maya denies visible world's value, while Ludendorff demands harmony: Faith/knowledge, blood-inheritance, rejecting superstitions for evolution-aligned cognition. ### Conclusion: Maya's Rejection as Emblem of Ludendorff's Vision Ludendorff's rejection of Hinduism, centered on Maya, embodies her philosophy's core: A racial-spiritual God-cognisance harmonizing empirical knowledge with Immortal-Will, rejecting illusions that disdain phenomena or impose alien dogmas. Maya, as fear-driven denial of visible reality, bars the research essential for Nordic vitality and divine perfection. By embracing the Erscheinungswelt as divine manifestation, Ludendorff envisions humanity's ascent to God's consciousness, free from primitive errors, fulfilling evolution's purpose in pre-death eternity. Her critique warns against spiritual passivity, urging active, race-conscious pursuit of truth— a call for Nordic rebirth amid cultural decay.

Comments

Post a Comment