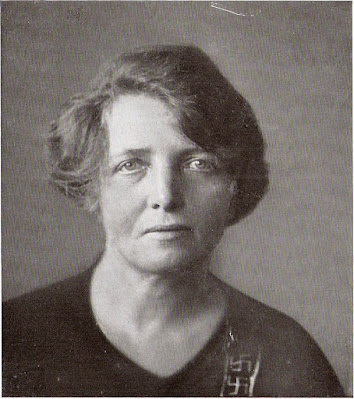

The Morals of the Struggle-for-Life - Part 7 - Book Review - Triumph of the Immortal Will by Mathilde Ludendorff

Summary of Mathilde Ludendorff’s Chapter: "The Morals of the Struggle-for-Life"

- Unreliable Conscience

- The human conscience’s relativity undermines moral development, as it varies by race, religion, class, and individual, often justifying atrocities (e.g., witch burnings). Mistaking it for God’s voice, reinforced by feelings of "good" or "bad" conscience, perpetuates moral confusion.

- Path to True Goodness

- Reliance on conscience’s fallibility (swayed by erring reason) must be rejected. God-living, not reason, redeems morality by revealing conscience as a mere rational tool, not divine. True goodness emerges from mistrusting conscience and aligning with divine wishes.

- Moral Categories

- Ludendorff distinguishes: (1) Duties-of-life (common laws for survival, e.g., self/family/folk preservation), (2) Morals of the struggle-for-life (practical efforts), (3) Morals-of-minne (spiritualized love), and (4) Morals-of-life (God-living). Past creeds mix these, stunting divine potential.

- Critique of Ten Commandments

- The Mosaic commandments blend duties-of-life (e.g., “Thou shalt not steal”) with divine wishes (e.g., Sabbath), corrupted by purpose (rewards/punishments) and dogma. Only one (Sabbath) aligns purely with God, while others reflect Indian/Persian origins distorted by Judaism/Christianity.

- Moral Confusion in Society

- Society praises "good character" (e.g., wealth-accumulating fathers, industrious housewives) based on struggle-for-life success, not divine cultivation. "Bad" characters include both degenerates and reformers, muddling moral estimation with utility over God-living.

- Work as Virtue Fallacy

- Elevating work to a virtue (e.g., for heavenly reward) confuses duty with morality, ignoring its amoral nature (self-preservation) or immorality (e.g., for riches/ambition). True moral work aligns with divine wishes, not societal praise or material gain.

- Order and Time Misconceptions

- Order (spatial division) aids beauty and survival (amoral), but overemphasis or disruption of God-living makes it immoral. Time-division (punctuality) is amoral, not virtuous; its rigid enforcement kills God-living’s timelessness, turning men into “chattering corpses.”

- Ambition’s Immorality

- Ambition, mixing divine joy-of-creation with beastly victory and fame, distorts genius. Rewards in education poison divine wishes, fostering immorality. True moral joy in creation is independent of external judgment or competition.

- Civilization vs. Culture

- Civilization (reason-driven survival tools) differs from culture (divine expression via art/science). Their conflation threatens culture’s suppression. Ludendorff’s morals harmonize them by subjecting struggle-for-life to divine guidance, preserving God-living.

- Charity and Social Morals

- Charity, rooted in divine pity, is often reduced to duty-of-life (self-evident aid), losing moral depth when indiscriminate. Social morals (respectability) prioritize utility over divine wishes, tolerating hypocrisy and degrading God-living to a performative act.

- Conscience’s Fallibility: Relative and rational, not divine, it misguides morality.

- Divine vs. Practical: Duties-of-life (survival) must serve morals-of-life (God-living).

- Moral Clarity: Distinguish struggle-for-life, minne, and God-living for true goodness.

- Critique of Tradition: Religious/civilizational morals confuse utility with divinity.

- Redemptive God-Living: Aligns human efforts with divine wishes, not rewards.

The great obstacle which has always stood in the way of

moral-development, be it the moral-development of whole races

or the single-individual, is the principle of relativity which

governs the human-conscience; this makes the 'voice of con-

science' unreliable. Notwithstanding this, a development in morals

could have been expected; for in reality, this feature is a great

blessing, as it alone affords man the possibility of becoming

truly good. Now let us see how this can happen. In the first

place it can prevent one becoming good or wanting to be good

in order to save oneself the torments of one's conscience, for

it alone makes the alternative possible which is the deadening

of conscience in order to escape its torments. The disaster, it

has worked, came about because of man's falling to the fallacy

that he could rely on his own conscience, as being the c voice

of God'. The belief in this fallacy was strengthened through

the feeling, called a 'good conscience', which came after a 'good'

action had been done. In this way the erroneous doctrine of the

"Erynnies" originated which belonged to the Greeks. The Eryn-

nies were supposed to be persecuting the evil-doer when his

conscience was tormenting him. Similar doctrines contained in

other religions were those which taught that the feeling of a

'good conscience' was the reward for a 'good deed* and a 'bad

conscience' for an 'evil deed*. Now, not until a man has been

able to fully realise that everyone, even the most immoral, can

be the lucky possessor of a clear conscience if he but take care

to keep his conscience free from the force of the moral-suggest-

318

ions which stand in contradiction to his actions, will he be

capacitated to forsake the wretched moral-creep of the quadr-

uped and erect himself walk upright like the real hyperzoan,

he is destined to be. The first step to spiritual-exfoliation is to

show the deepest mistrust towards one's own conscience, for

the simple reason that it is swayed by the force of reason and

can therefore err.

The most degraded of men might examine the state of their

own conscience and, in the fullness of their self-satisfaction say;

"behold, it is good", if when judging, they have taken their

own warped moral conceptions as the measure. If we could but

find reasonable definitions of absolute validity for each individ-

ual case, it would be a trivial matter to put an end, once and for

all, to all the unreliable judgements which prevail. But as this

is impossible, (as we have already been able to sec) the con-

sequences are, that the most confused conceptions are mixed up

with the word 'good'. History gives abundant examples of this.

The burning of witches at the stake, and the massacre of millions

of heretics and researchers etc. will suffice to show what is here

meant. Hence we repeat again: Not reason, but God only, can

be the redeeming factor here; God-living alone is capacitated to

liberate man from the error which he has been persuaded to

believe when he thinks his conscience is the "Voice of God",

or the "Holy Ghost", and the "Pricks of Conscience" the just

punishment for evil doing, and the trust he puts in its reliability.

God-living only can reveal to us that our conscience is merely

one of the many instruments of our reason, the duty of which

is to inform us whether our actions conflict or agree with the

conception our reason has formed of morals. This will help

to explain why a Chinese can do things with the clearest con-

science which would torment a Christian with the greatest qualms

of conscience. Why we, in the fullness of our God-Cognisance,

are obliged to call certain actions of Christians "Murder" which

they think to be "Pious deeds". But not only according to race

and religion does the voice of conscience show its variety, it

differs also, in that the morals of class, family and individuals

differ.

In order to avoid the unreliable and come instead to the

reality of what is good, deeper insight is requisite. Above all

it is very necessary to know why death is compulsory, what the

meaning of life is, and why immortality takes place before

death, whereby, the preservation of self, family and folk become

duties of a most sacred import, in that they are made subject

to the divine-will, and therefore included in the wish-to-be-

like-God.

According to these truths, each individual of his own accord

will come to weigh his actions. Values will then fructuate, the

nature of which will be more and more identical with God. In

this endeavour we can be supported greatly if we live con-

sciously according to the divine-wishes The more we dedicate

ourselves to the life in God as being the essence of life, the less

we shall allow ourselves to become influenced by the confused

moral standards which call moral actions bad and immoral

actions good. The nearer too shall we be able to approach that

state of perfection from the vantage of which, we can regulate

our lives, with a somnambulic sureness, according to the divine-

wishes and the above mentioned truths. The more we try to

keep the divine-wishes alive in our souls, the easier we shall

be able to discriminate if the moral-conceptions, we have formed

by means of our reason's potencies, are likely to further the

divinity innate in action or not.

To escape from all confusion, it is essential, at first, to be

able to discriminate between morals altogether. There are the

morals of the struggle-for-existence, the morals-of-minne (the

more spiritual ised-love) arid the morals-of-Godliving.

In the field of the latter divine free will reigns supreme.

320

Right up till now, all the moral-doctrines, contained in the

diverse religions, philosophies and natural-sciences, are stigmat-

ised with just this lack of discrimination. One and all reveal

a mere motley of doctrines. There are those serviceable to the

struggle-for-life, sexuality, the life-preservation of self, family

and folk; which are merely duties and therefore belong under

the heading "Common Law" or the "Duties-of-Life" and then

those pertaining to the wishes of the divine-Will, which I have

reserved to be called alone the "Morals-of-Life", Godliving or

morals of life. Finally, there is still to be found a few dogmat-

ical and cult-commandments mixed up with this motley of

creeds. Then again the materialists on the one hand, take only

a small part of the duties pertaining to the common-weal into

consideration, especially where the duties of self-preservation

are concerned, while the philosophers on the other hand take

only a part of the range where the divine-wishes come to light

into sufficient consideration; as for example, Schopenhauer, who

was taken up in particular with the urge which men reveal to

come to the aid of their fellow-men, out of which the virtue of

charity is born. Especially in the misconseption of the morals-

of-life, as well as the duties to the common-weal governing the

life-preservation of self and folk, the "World Religions" did

infinite harm in that they pandered to deterioration of race.

("The Folk-Soul and its Modellers.") The 'conscience' of all

those religious-adherents could not have been led more astray

than it has already happened under the inducement of such a

motley of moral suggestions. The commandments given to Moses

is one of the best examples for the motley of moral command-

ments we have just been treating. Now, since 2,500 years, these

commandments have been the foundation of the Jewish religion,

and since 2,000 years they have played an essential part in the

Christian religion. Even still they are allowed to exercise their

influence over the 'voice of conscience* in our little ones. As I,

myself, have laid down moral-values (as the issue of the truths

I have been able to perceive) and, on accord of the solution

which these have afforded in solving the ultimate mysteries of

life, I am also obliged to take up a criticism of the moral-

demands prevailing to- day.

Note: These commandments, like all the other commandments

of Moses, were written down by Esra in the year fivehundred

A. D. He mostly copied them from the Books-of-the-Law be-

longing to the Persians and Indians. I have given full witness

to this in my other books. (S. book list).

1st Commandment: "I am the Lord thy God which have

brought thee out of the Land of Egypt,

out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt

have no other gods, before me etc." A

dogmatic instruction of Monotheism, as

well as a nice little reminder of the bene-

fits God once bestowed, fill the contents

of this commandment.

2nd Commandment: "Thou shalt not take the name of the

Lord thy God in vain, for the Lord will

not hold him guiltless that taketh his

name in vain." The contents of this

commandment is morally degraded

through the pursuit of intention which

it reveals and therefore, morally speak-

ing, is of no value. It was once a cult-

commandment originating from the fear

of demons. At the time Esra wrote it

down, the conception prevailed that in

the calling out of its name a demon could

be disposed of.

3rd Commandment: "Remember the Sabboth day, to keep it

holy, 6 days etc." This is a divine- wish

4th Commandment:

5th Commandment:

6th Commandment:

7th Commandment:

8th Commandment:

as it calls men to God, but is spoilt

through the command it gives sound to.

"Honour thy father and thy mother, that

thy days may be long upon the land

which the lord thy god giveth thee",

belong partly to the duties-of-life owed

to the common-weal in its demanding

subjection, and partly to the laws-of-

God, but which is spoilt through the

promise of reward, as this indicates the

pursuit of purpose.

"Thou shalt not kill", is one of the

duties-of-life owed to the common-weal,

but put in a completely immoral way,

as it does not provide for folk-defence

in the event of war nor self-defence in

the case of emergency.

"Thou shalt not commit adultery" is a

divine-wish, although lessened in its va-

lue through the words 'thou shalt' and

also a duty-of-life owed to the common-

weal.

"Thou shalt not steal" is one of the

duties-of-life owed to the common-weal.

"Thou shalt not bear false witness

against thy neighbour" could have been

called a divine-wish, had the words

'Thou shalt' and 'thy neighbour* been

left out, for these represent both a com-

mand and a limitation which should not

be, and is therefore a part of the com-

mon-duties (common law), owed to the

common-weal.

3*3

9th Commandment: "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's

house etc." is a repetition and extension

of the 7th Commandment, in that it

points to the sin which can be committed

'in thought' also. Thus also it belongs

to the duties owed to the common-weal.

10th Commandment: "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's-

wife, nor his man-servant, nor his maid-

servant, nor anything that is thy neigh-

bours." This is a repetition and extension

of the 6th and 7th commandments, and

therefore belongs also to duty (common-

weal).

Now of all these ten commandments (which in religious in-

struction, by the way millions are made to believe, are the

veritable foundations of morality) two repeat themselves, so

that in reality there are only eight instead of ten. And among

these, only one (keeping the sabboth holy) can be said to be

a pure and disinterested divine-wish, because no purpose is

attached. Three of these commandments are mere claims which

the common law makes on mankind, and as such are self -under-

stood. In fact the penal-law of our state demands their fulfil-

ment. Therefore they have no right at all in religious instruct-

ions. As for the rest; one commandment is a dogmatic claim;

a second, a divine-wish (corrupted, however, through the pro-

mise of the reward it contains) as well as being merely one of

the duties-of-life; a third prohibits the calling up of demons;

and a fourth a divine-wish corrupted through making a com-

mand of it and a duty-to-life (common-weal); "Thou shalt

not commit adultery and thou shalt not covet they neighbour's

wife" sound particularly edifying, when heard from out the

lips of a young child. Altogether the conceptions, contained in

the ten commandments, seem nothing but a mass of confusion

3*4

when seen in the light of our philosopny. Yet historical value

at least could be procured for them, were the children taught

that they were extractions from the laws composed by the

Indian Manu; laws which in themselves were partly of a very

exalted kind and partly very profane. In every case this would

lead to a better understanding of the tremendous insight into

truth which, in the course of the long centuries, man has been

led to gain under the guidance of the divinity within him. But,

unfortunately, our children hear nothing of the like. On the

contrary, instead of hearing that the commandments (as we

have just said) are merely distorted extractions from the law-

book of an Indian, they are told, that the ten commandments

were revealed to Moses by the God of consummate excellence.

Owing to this fact, these commandments become the very cause

of the confusion which often goes on in the child's breast and

which hinders it in developing spiritually. More often than not

it is the very cause why the lowest stage can never be surpassed

a whole life long.

Innumerable examples of the like kind can still be found

which have their cause in the unutterable moral-confusion of

the prevailing creeds. From the same cause the general estimat-

ion of character is also made up of a motley of truth and error.

Just observe for a moment those men who are standing upon

the top-rung of the moral-ladder. They are thought to be men

of 'good' character, or honourable men, not because they have

cultivated the divine-wishes within them, for, on the contrary,

they have stunted them; and not only because they have hon-

estly endeavoured to gain a living for their family, but simply

because they have succeeded in amassing the family-fortune.

Look how they walk through life in the firm belief their

characters and achievements are "Good". Their self-satisfied mien

plainly reveals it. They are believed to be the 'clever, smart,

dutiful family-fathers' and enjoy the admiration of all around

them. Along side of them, on the very same 'high rung* of the

moral-ladder, housewives will be seen standing. Now observe

how little the divine-wishes are alive in them, but how the

more industrious they are in the welfare of their family, yet

not to keep God alive in the members of their family, nor in

the work of gaining the bare necessities of a living for them

(these would be noble purposes), but all what seems to matter

to them and on which their minds are solely bent is the preparing

of the meals to the enjoyment of everyone's palate. On that

peculiar moral-ladder, where the men stand blessed with a 'good

character', others, of-course, are suffered to stand as well, but

lower down, as long as these fulfil the demands which the

struggle-for existence makes on mankind. There God-living

matters little in men's estimation of them here. Moreover, among

the group of 'bad' characters, there can also be found the same

kind of mixed society. Among these 'bad' characters some are

called 'antisocial', because of their disrespect for the ordinary

duties of mankind; there is no distinction drawn between those,

whose convictions are due to genius being very strong within

them, albeit the sense of their direction may not be divine, and

others, who in the greed for money and through the degener-

ation of their instincts, disrespect indeed the sacredness of the

common-law. The most curious of all among the crowd of 'bad*

characters, however, are those individuals whom the super-

ficiality and confusion of the prevailing morals fill with indign-

ation, and in wanting to 'better the world' endeavour to release

mankind from the fetters of the prevailing ideas in that they

themselves strive to give the example of a new standard-of-

morals.

Hence, as all this means that the claims of God and the

claims of gaining-a-living have become so entangled, the only

way to find a solution is to treat each different claim separately.

We must make a clear distinction between the claims God makes

326

on the struggle-for-life and the instincts of man, and God-

living of man Itself. The aim of the latter is the strengthening

of the divine-wishes of the divinity within man's soul. There-

fore we must necessarily classify our code of morals as follows:

Duties-of-life: (The common-laws owed to the common-weal

as being thought of as the unwritten laws-of-the-land), the

morals of the struggle-for-life, the morals-of-minne (the spirit-

ualised love) and the morals-of-life.

It was fatal for the religions not to have suspected the evolut-

ion of man from the animal; not to have known of the spirit-

ual inheritance which the animal had bequeathed to man, for it

bereft them of the most important hypothesis. It was natural

therefore they should remain ignorant of the fact, that the

instinct which forced the animal to preserve its own life and

that of its kind had to be made up for somehow in the human

community; therefore laws to this effect, under strict penalty if

neglected, could be the only recompense for the lack of the sure

instinct which the animal possesses. I call these laws the Duties-

of-life. They are completely different in their nature to those

moral-laws I have called: the Morals-of-life. For the trait of

divine voluntariness distinguishes the latter, that means to say,

neither punishment nor reward has any influence over them;

divine free-will, the aim of which is to bring man's will in unity

with the will of God, is supreme.

These special duties, (among the range of the duties-of-life,)

which answer to the purpose of preserving the life of self, family

and folk as well as preserving the spirit-of-God in the single

individual, we cannot stop to treat here. Space has been given

to them in the second part of my triple-work entitled "Works

and Deed of the Human-Soul". The main points have been

clearly and briefly indicated with the aim in view of being

comprehensible to everyone in a booklet, entitled "Extracts from

the God-Cognisance of my Works".

3*7

However, the point we should like to lay stress on in this

book is, that the morals-of-minne (the sublimated sexual-will)

and the morals of the struggle-for-life should always be sub-

jected to the divine-wishes with the aim in view of giving divine

sense to our lives.

Knowing what the meaning of the life of man is, and what

the animal's struggle-for-life means, it is clear that any errors

arising in this respect will always stand in the way of man's

living the life in God. In our observation of the animal-king-

dom, it has been clearly revealed to us how much easier the

struggle-for-existence, in the way the animal fights it, can har-

monise with the divine-wishes. This is because there is no other

aim than the one to preserve life, so that, except in cases of

emergency when cunning is made necessary, hypocrisy is un-

known. Thus our morals of the struggle-for-life make a peculiar

demand on mankind: Forsake first the path of degeneration

and confusion and return again to the amoral nature which

characterises the animals' struggle-for-existence.

How did the perils of degeneration arise? Like this. Through

the power-of-memory the experience of every and sundry joy

or pain could be held fast in the grasp of conscious remem-

brance, and, through the power-of-reason, experience was gained

respecting the rules governing the cause of happiness. The results

of this were that a novel kind of struggle-for-life arose, which,

although quite unknown among the animals, was possible in the

life of men, notwithstanding the fact, that their intelligence

had little of the nature of the divine. This was characterised

by the struggling endeavours to enjoy as much and as often as

possible. By and by this novel type of combat came up to the

front and takes up the most part of man's life, although

curiously enough, through the development of his reason, the

actual struggle-for-existence had been rendered decidedly easier.

But of this fact men seem completely oblivious. They struggle

on untiringly without once stopping to sink into that stately

attitude of peace which so beautifully distinguishes the animal

when its labours for a living are over for a while. Men drive

on from one state of pleasure to another. Instead of a just

appeasement of hunger, the indulgence in too much and too

good eating has become the ugly habit. Sexual-communion takes

place, not in that holy spirit which strives for the maintance of

the kind, but merely to indulge in the lewdness-of-lust. For such

purposes the possession of riches, of -course, are of great import-

ance, for riches make a man independent of working for his

living as well as give him the facility to prepare and heap up

pleasure for himself. To slave a life long for this aim is

generally 'understood* to be the right thing to do.

In still another respect has reason been able to transform

life. When families gathered together into one folk-body to

be ruled by a 'state', the consequences which arose were obliged

to be different from those which arose in the animal-kingdom,

as men were endowered with reason. Of- course, in the human-

state individuals also work for the common-weal. But as the

possibility always remains for the individual 'servant* in the

state to be full of that novel instinct of man's own invention,

that is, the chase after pleasure and amassing of fortune in order

to escape working for a living, (all of which he can do at the

cost of his fellowmen through the potencies of his reason) the

unjust division of property was obliged to make its appearance

in the human-community. So it came about that while some

could amply satisfy all their desires, others had to work hard

for the bare necessities of life. These abuses can have the support

or the rejection of the state, but never will they be completely

eliminated from human society, until each individual man has

succeeded in changing his mode of spiritual-life, that means to

say, until he stops his chase after mere pleasure, or in better

words until he stops being merely a 'fortune hunter*. Now those

who are acquainted with the laws which render the soul's 'im-

prisonment' which I have taken particular trouble to explain

in the third book entitled "Creation of Self" of my triple work

"Origin and Nature of the Soul", will hardly be inclined to

believe such a change can be brought about in the soul-life of

man. But our God-Cognisance has indeed the power to redeem

man from his pursuit of happiness; its fruitful influence, in

this respect, works more to the improvement of these human

grievances, than any change which the law could bring about.

Now, as it proved impossible in the past to evade the in-

justice of overloading the majority of intellectual and manual-

workers for the benefit of the few, ways and means had to be

thought of in order to give these unfortunate ones a sort of

recompense for the disproportionate remuneration which the

state was rendering them for their services. So, in order to keep

them going cheerfully, mere work was raised to the standard

of virtue in that it was made to believe that work was born of

the Wish-to-Goodness, and as such was an action of a divine

nature. This was a pernicious thing to do and has caused much

confusion in man's moral state as a consequence, as well as it

has helped greatly to stunt the divine wishes within him. It was

thought that as the wish in man to be good is closely connected

with his Immortal-Will, (this we have already clearly perceived

to be true) the possibility was given him to earn immortal-life in

'heaven* through the diligence of his work. Therefore, work

became a duty which in reality was a mixture of moral as well

as immoral achievements, instead of the duty it is which is to aid

in giving a deeper sense to the lives of men, in that it serves

in the maintenance of self, family and folk. This fallacy would

never have gained such a hold on the minds of men, had it not

been for a twofold circumstance which made it appear so essent-

ial and desirable. While.the animal is only allowed a very

short time to remain under its mother's care, to have then to

33

take up the struggle-for-life itself which means it must search

for food and defend itself in danger; with man the case is differ-

ent. Owing to a much slower process of development, the child,

fortunately, is spared the trouble of gaining a living for many

years to come. Parents take this trouble off the child's shoulders.

This, of-course, is of vital importance in the development of the

divine-wishes in a child, but which also can bring harm. I have

fully treated this subject in "The Child's Soul and its Parents'

Office". It can be the cause of the child taking it for granted

that the endeavours to gain a living should be taken off its

shoulders, as the impression of its childhood can be retained

consciously in its memory. As it is, men in general, are apt to

consider their work, in the endeavours for a living, to be a

great 'achievement'. In this judgement, they are often supported

by the trait of inherent laziness' (indolence) which they have

inherited from the animal-world and which is still greatly in-

dulged in, inspite of man's greed for pleasure, as only danger

and hunger seem capable of overcoming it. Now, to come back

to the young child. As it receives from its surroundings the im-

pression that, in the aim for a pleasurable existence, utility in

the struggle-for-existence is the most important, it is only natural

when it exhibits a habit of indolence at school in subjects which

are not exactly associated with getting-on in the general struggle-

for-existence. Of-course the great mistakes made in the choice

of educational-subjects, and the peculiar manner in the system

of teaching (pedagogic), are also causes for the indolence of

children. (See the above mentioned book, chap. "The Sign to

Knowledge" and "Modellers of Judgement".) Thus then, in

order to inspire diligence, the most potential means are requisite;

the child therefore receives the instruction, both in the form of

poetry and prose, that work has its reward. Both heavenly and

earthly gains are the recompense.

The preaching, that work was a virtue, found substantial

support in the divine-joy-of-creation which is one of God's

wish-fulfilment. Now, through that confused moral-conception

which told that all kind of work was in itself virtue, this joy

was extented to every and sundry achievement, so that every-

thing done was accompanied with a 'good conscience'. Besides

which, the favourable effect which work had on men of a lower

standard (Carlyle) convinced men all the more that work in

itself was a virtue. Undoubtedly it was true, that through work

the dangers could be evaded which sprang from degenerate in-

stincts (due to reason). For instance, the distraction from the

sexual-instincts, and the weariness which overcomes the body

after hard work has been done obviously helps to keep down

the strength of the temptation, in much the same manner as

sport effectively influences the really indolent who absolutely

fight shy of work; so that it goes without saying, men will

always be tempted to believe that every kind of work is the

greatest blessing in the life of mankind; is it not like the 'mag-

ician* who can drive away c evil spirits'? Now, in reality, work

succeeds very little in vanquishing the 'evil spirits'. At the best,

it can only hide them from the world around; the greatest

industry will not prevent them working their evil way in a

man; so that it often occurs that they revenge themselves for

having been hidden so long, when then an unbridled beast of

prey can be born. There are other kinds of 'evil spirits' which

are not connected with sexual-instincts, but which work is still

less capable of keeping down. On the contrary, the doctrine

that all kind of work is a virtue, has been such an incitant, that

infinite harm has been done. For instance, how many industr-

ious persons there are, who, through the good opinion they

have of themselves (good conscience) and the favourable public

opinion which surrounds them, are seduced to give way to the

most obnoxious trends in the passion they show for work!

Notwithstanding the success achieved already in having raised

33*

work to the pedestal of virtue, there was still very much evil

left for the state to rectify. So many sacrifices were being made

daily, for which meagre wages and the protection of the law were

a poor recompense. Innumerable individuals were kept at work

like ants to break down in the end exhausted. Work is a 'virtue'

had its effect only, where the really noble-minded were con-

cerned, in whom the desire to be good (the divine Wish-to-Good-

ness, as we have termed it) was inherently strong. On all the

others in whom this characteristic was absent, its effect was lost.

They were doomed to become inevitable failures. And so it came

to pass that the cunning mind of man invented another moral

'trick* which undoubtedly was also crowned with success; it

caused men to gain amazing achievements. Although more than

anything else it was the cause of man's degeneration! Like into

a witdiVpot human sentiments were thrown. The divine-joy-

of-creation was mixed together with the ancient joy of the

beast when it gains the victory over its enemy. To this, the

poison called 'fame is immortal* was added. The result was

the mixture known as 'the sane ambition* which, curiously

enough, men also ventured to raise to the pedestal of virtue. As

the trend-to-indolence (one of the heirlooms inherited from

the beast) is stronger in man, than the trend to ambition, the

first often kept the latter down in the case of such individuals

for whom, in the first place, it was intended; but as a state

which is made up out of a confusion of moral-laws is very

dependent on the workings of ambition, it was seen to, that

this particular trait should start its development already in

the little child. To this purpose awards and rewards were in-

vented which hardly ever failed in their effects; for by the time

a child had grown up, the divine-wishes had been poisoned

or trampled down by the aims of ambition, as many persons

around us reveal, who are nothing more than unwise schemers.

The worst evil among the many is this one however: When

333

ambition was awakened and kept alive in the young, it was not

only to answer its purpose in respects to achievements which

should make the struggle- for-life a success; it was extended

equally to the achievements which have their origin in God. In

passing, tutors make themselves accomplices of evil-doers when

they neglect to tell their pupils that ambition kills the spirit

of God within us, in killing divine talents which are the be-

ginnings of those divine-potencies of creation in later life.

Now, what do our morals say to all this confusion? When

ambition is mentioned which to God is the deadliest enemy of

all, they say: No moral value can be attached to the joy -of-

creation in, let us say, works-of-art, or in the ordinary achieve-

ments concerned in the struggle-for-life, unless the wishes of

the divine-will are fully considered, that means to say, the joy-

of-creation must be subordinate to the divine-wishes. (We shall

come back to such kind of labour very often in the course of

this book). But this moral-joy will reveal itself to be utterly

independent of the achievements of others. If they surpass it,

it will not be ashamed; if they are surpassed, it will not feel

proud. Neither is it shaken in any way by the 'judgement* which

public opinion falls on it. It is immune both to 'fame' and mis-

understanding. The first does not serve towards its development,

nor can the latter destroy it. But ambition which can be easily

recognised because its behaviour is so different to this is great

immorality, because it distorts and kills genius. If the powers

that be, allow children to be brought up at school to depend

on awards for the joy to achieve or in a spirit-of-desire to 'beat'

the others, instead of cultivating the divine spirit of moral-joy

in achieving, merely because of its own virtue, commit a great

crime against the God in the human souls which have been

entrusted to them. It is true, many persons would rather sun

themselves tranquilly (as the lion does in front of its cave),

than give themselves up to painting, poetry, scientific-research,

334

fighting in a good course, or dangerous sport just for the sake

of fame. But one thing is certain, none of all the folks of the

earth, our own included, will ever be able to recuperate from

the evil effects of degeneration, until these evil spirits men have

called up have been put again into their graves for the dead

things which they are.

Considering the infinite harm which the evil spirit of ambit-

ion does to genius in man, award, in the support of this, for

achievements which belong to the spiritual-world should be em-

phatically discarded, more so, as true genius is above reward.

And now, the holy meaning of human-life and work as a

virtue. What has this truth of our cognition to say in face of

this error? It acknowledges that work can be of a moral, immoral

and amoral kind, that means to say, there is work which is

good, work which is bad, and work which is neither good nor

bad, but which is self-understood, the neglect of which however

would be bad. For example. Work in the natural endeavour

(in the sense the animal does it) to gain a living for oneself,

one's own and one's own folk is the amoral fulfilment of the

duty one owes to on's kind and the preservation instinct of

self and is therefore selfunderstood. Neither "God nor the devir

are touched at the sight of our endeavours in the search for food

to keep ourselves and our children from starving. A state of

indolence which would prevent us from fulfilling this duty

would consequently be immorality. When all the cunning tricks,

which are used to rob the state of its due and which pillage the

working-populace, are once and for all eliminated (these render

life so difficult), and squalid overpopulation is no more, then

sufficient scope will be given to the divine- wishes inspite of

this work which has the nature of being a matter-of-course. In

order to discourage 'laziness* (which is immoral behaviour) the

morals of the struggle-for-life demand from every healthy adult

335

who has the protection of the state to earn his own living and

to look after the welfare of his children who are still under age.

All other kinds of work may be moral or immoral as the case

may be. It bears the moral character when it is completely sub-

jected to the divine-wishes. It bears the character of immorality

when it goes contrary to them. Now, God wills the life of each

individual person, that each may participate in the Immortal-

Life, (exceptions exist which we shall learn about shortly).

Therefore the work, undertaken for a man to be able to live at

all, can never bear the character of immorality, although the

same kind of work is immoral, if it is done in order to gain

superfluity of riches, especially when these are put to no good

purpose either for the one who possesses them or those around

him. All work fraught with the purpose of satisfying a man's

ambition or vanity is likewise an immoral endeavour. Observe

then, that whenever a thing is about to be done, our philosophy

asks first if it is moral or immoral. All labour, of each and every

kind, must be weighed according to the scales of the Divine-

Will and that meaning of human-life which we have grown in

knowledge of. Industriousness in the cause of immoral work is,

of course, always immorality. A man must fully weigh before-

hand and then give his promise to do the work which as a 'duty',

he then takes upon himself. According to these new rules many

would have to climb down lower, who, to-day, stand at the

top of the moral-ladder. But on the other hand, it would bring

mankind benefit, in that all would surely be more careful and

critical about the aims he intends following in life. How many

parents, for example, are there, who strive from morning until

night for the welfare of their children, and because they grudge

themselves every bit of pleasure in this endeavour, they imagine

their behaviour to be so 'good'. They heap up wealth in order

to leave it their children, and in this industrious endeavour they

forget all about God which calls for development in their own

33*

breasts; in fact, in the one endeavour hardly time or power is

left them to be able to support the development of the divine

wishes in their children either. Then, from the example they

give, their children also learn to consider goods to be of the

most vital importance in life and, under the sway of such ideas,

begin to smother the kernel which contains the essence of divine-

life in their souls. Hence, the results of the parents' 'life of

selfsacrifice' is the death of their own soul as well as the death

of the souls of the children committed to their care.

When we stop to think what else men have made a virtue of,

we shall soon see, that, besides having made a virtue of work

which they believed effected the amassing of pleasure if governed

by the principles of 'practicality and utility* (a complete mis-

understanding of causality) they have also made use of the

other two forms of thought, called time and space. Actually,

the rule of order and time have been created into virtues just

like men made a virtue of practical work. In reality, thess:

faculties are of minor importance, as they are as liable to disturb

as well as aid the development of the divine-wishes within man.

Under the impression of such a misconstruction of these facts,

parents are apt to consider the disrespect of the divine will of

less harm than the neglect to divide life into time and space,

despite the fact of the warm intention they have to save the

soul-lives of their children.

The logical division of things in space is called 'order', and

order of every kind is called 'virtue'. It can become the 'blessed

daughter of heaven' as Schiller called it; in reality, however,

it is the 'blessed daughter of reason' and can become neglected

from a twofold unequal cause. The first cause is the indolence

native to man. The animal inevitably sinks into the original

state of tranquillity as soon as the pangs of hunger and the fears

of danger have passed. This feature it has handed down to

mankind. Indolence prevents a person being orderly. The second

337

cause very often arises when men participate much in the life

of God. Their sense of order then lacks its keenness. It is

alarming sometimes to find this 'daughter of reason' absent in

men of genius, for a disorderly habit is often the cause of the

disturbance to their God-living which, as a consequence, they

not infrequently experience. The "God that reigns free in the

Ether" must indeed feel beseechingly helpless towards objects

limited to space! Men who are blessed with a keener sense of

the divine are often quite oblivious to ugliness, a fact which

we have already spoken of. This also can cause them to be

disorderly, for one is obliged to be aware of the disorder, in

order to avoid it. The reason why they are not capable of seeing

it is, because order is generally connected with beauty, and dis-

order, therefore being ugly, is for them the 'nonexistent* gener-

ally: It is not perceived. It is not curious then to find them, in

unexpected moments, intensely busy putting things in order,

for they are the moments when they have come back again to

earth. Their bad sense of order is greatly aggravated, of course,

because their spirit is always beyond the limits of space when

they are participating in the divine life and are at work for it.

In the confusion of men's ideas, little thought has been given

to find out the real cause of a man's disorder. This accounts

for the reason why the sober, matter-of-fact strugglcr-for-a-

living to whom the objects surrounding him are essential parts

of life, shows contempt for the man-of-genius for the same

reason as he despises the indolent. Moreover he lustily supports

that fallacy which is, that 'a man who shows sense of order must

also be a moral man', whereas in reality many lovers of order

are completely soulless and sometimes morally degraded as well.

In contradiction to the doctrine, 'order is virtue* our morals

say:

One must strive for order, as it is related to the divinity

338

in perception which manifests itself in the divine Wish-to-

Beauty. As long as it aids in the fulfilment of this wish it bears

the character of morality. Furthermore it is of advantage to

man in his endeavours to gain the necessities of life which is

important again for his Godliving and is therefore amoral, being

selfunderstood. In such a case, disorder would bear the character

of immorality. Finally, the state of order facilitates God-living,

a fact which will become clear to us as soon as we think of

all the time lost in search of objects which men-of-genius en-

counter through their own disorder. Order gains importance

when it aids and supports Godliving; to neglect it, in such a

case, would be immoral. Moreover it is acting immorally, when,

through disorder, we disturb the necessary struggle-for-a-living

or the Godliving of our fellowmen. Likewise we would act

immorally if, through commanding order, we arc likely to dis-

turb or encumber the Godliving of another. Thus then, in diverse

cases, order can be immoral, but, on the other hand, the state

of order or when it is demanded from another can be moral,

if it is the fulfilment of the Wish-to-Beauty. It is always

immoral, in every case, when it does harm to that in man, what

we have called the life-beyond, the life in God or "Godliving*'.

The division of time, that is, the logic distribution of activity

and repose according to the beat of time, has also been given

its value. Curiously enough, however, a 'virtue* has not been

made of it, like man was bold enough to do with order. What

could be the reason? Is it because the division-of-time was not

so closely related to the Wish-to-Beauty like order was? But

there is no evidence of this connection having been recognised

in the past. Exactly as it was unknown that the moral-state

demands the development of all the divine-wishes and not the

Wish-to-Goodness alone which also means that the Wish-to-

Beauty would not have the moral nature, did it stand in the

339

way of any of the other divine-wishes. Therefore this evid-

ently was not the reason. The division of time cropped up

much later than the division of space. Not until the increase in

population as well as other matters which rendered the struggle-

for-existence so difficult, did time-division gain importance.

Nevertheless the division-of-time has grown to be highly estim-

ated. What does our philosophy say to this?

As the division-of-time is not directly connected with the

divine-wishes, it cannot be classified among the morals like or-

der. In respect, however, to the essential part it plays in the

general struggle-for-life, it becomes a self understood matter and

therefore has the quality of being amoral. Its absence in such a

case, would mean immorality. If time and peace are made wan-

ting for the benefit of Godliving through any neglect of time-

division, this also becomes immoral. Finally it is immoral, if,

through negligence of time-division, the struggle- for-a-living or

the God-living of another is made difficult. Thus then, it is possi-

ble that the neglect of time-divison can become immoral, while

time division itself can never be classified among the morals. It

is amoral always and becomes immoral only when it is a disturb-

ance to Godliving. Now, in such a time as ours, when life is

minutely divided, it is of the greatest importance to understand

the weight of such immorality, how necessary it is to perceive it

brings about the death of God in man; for the growth and life

of God depends on the oblivion of time in order to find entr-

ance into the realms where time is not. The life of God is time-

less and must be so. Therefore it is futile to want to subject it to

the time of the clock. What a blessing it is that men are not able

to calculate how much of the Life-of-God has been destroyed

through the ticking and striking of clocks, or they might be

tempted to forget their usefulness and smash them in their

anger. Happily the God-loving man experiences no difficulties

in entering timelessness. The greater his development is in the

340

progress of his diviner-nature, the easier this becomes, so that,

despite life's necessary division-of-time, his God-living is safe,

provided of course, there are none of those untiring worldly

strugglers near to disturb his peace. For in them he will find no

sympathy at all for the slowness which he exhibits sometimes in

getting on in the world. They call it waste of time. And time is

money they think. I have called them "the Chattering Corpses"

(they really resemble ticking clocks) to distinguish them from the

God-living man, who is animated with the spirit of God. It is

funny to watch these cut up their lives and all the soul-exper-

iences life contains according to the inches of a tape-measure, so

to speak, but shocking when they dare to disturb others in the

participation of the Life-of-God and that with a good con-

science, merely because they think it good when some trivial

thing should be seen to at any a precise moment. There was

once a time, however, when even the chattering corpses were

capable of forgetting the beat of time; that happened in the

dreamland of their childhood. But the struggle of later life sober-

ed them all too soon, and because they have forgotten how to

get rid of the fetters of time, they are anxious of the quick flight

it takes. They are only aware of the fleeting side of its nature

unlike the Godliving man who is so often priviledged to partake

of life eternal. The more the spirit of God exfoliates within him,

the greater the length appears of the years that are passing. To

the chattering-corpses each year seems to pass more quickly, the

farther they leave the life of youth with its affects and dreams

behind them, and the less scope they can give to their own

imagination (Phantasy). An interesting fact which one can note

in all educational institutes, when the aim of which is to mortify

the soul, is, that all the occupations are divided strictly accord-

ing to time. One occupation will be suddenly stopped to start

another. Even prayers start precisely at such and such a minute.

These are the most efficacious means in bringing them towards

their ends. Note, for example, the Jesuit colleges, the aim of

which is to bring up young priests to be "Loyala's Corpses".*)

Notwithstanding all this, men have forever suspected that an

animosity exists between God and the habit which man has

grown into of dividing up time and space. Yet this caused but

another error. That the division-of-time and space was consi-

dered a 'virtue* was indeed a false conception, but another had

to be added which was, that, disorder and carelessness in the

division of time was a sure sign of genius. Many an artist and

researcher, in the plenitude of their divine talents, succumb only

too gladly to this error. They are all too ready to be blind to

the fact how badly they have trained their own will to discipl-

ine, how degenerate they have allowed their instincts to be-

come, and how weak they are in action, and how all this, as a

consequence, makes them unfit for the struggle-for-life. So they

shift the fault to their own genius and squander their time in in-

dolence or in the lust of their passions, instead of living and

working in the development of their genius.

And now we come round to our morals of the struggle-for-

life. These tell us to beware of indiscrimination and not call

every kind of work, diligence, order and punctuality a virtue,

but instead to consider carefully each individual case in the light

of the divine wishes and the meaning of life.

Among all the claims which reason put to the individual, when

men of the same folk clubbed together and respected each other

as a community, one seemed particularly to appeal to them. It

was, 'do to others as you would be done by'. We have already

traced the origin of this. (See above.) Now, in as much as this

law (The duties-of-life) became gradually consolidated, in that

it extended its protection to property and life so that family and

folk-preservation was assured, its dutiful fulfilment, notwith-

4 We refer the reader to the book .The Secret of the Jesuits' Power and its End", dupter .The

Training in the black Kennels".)

34*

standing, did not raise man above the moral zero point, although

the neglect to fulfil this duty which is in the interests of the

common-weal is decidedly immoral. Nevertheless, great import-

ance must be attached to the fulfilment of this duty, in as much

as man's participation in God greatly depends on it, although

the impediments to God-living which the common-law (duty)

eliminates would not exist at all, were man living solitary, in-

stead of in community as he does. What religion has taught up

till now as being transgressions against the duties-of-life, when

looked at from the light of life's meaning, is immorality, and as

such must be rejected, for, from our philosophy's point of view,

the subordination of divine deeds which issue from the divinity

in man to the results which issue from reason may never be;

every demand which the duty to life makes on us, must be close-

ly scrutinized in order to assure ourselves if its fulfilment would

be in harmony with the divine Will, in which case it would be

amoral and in the contrary case, immoral. We have drawn lines

to work on in this respect in the following chapter "Morals of

Life". Here the demands belonging to the duty-to-life have been

made sufficiently clear, so as to be a guide to action in the happen-

ings of any event, yet leaving scope for the individual to think

and judge for himself which is a matter of infinite importance in

the development of Godliving.

Among all the morals of the struggle-for-life which are in

practice to-day, there is only one which has a distinct touch of

the divine. It has already been often mentioned. It is the 'charit-

able deed', born of the feeling of pity, which has its origin in

the one divine emotion, the feeling of love towards one's fel-

lowmen. Yet, when looked at more closely, it will be found, that

there is still much to be rejected as being inadequate to fulfil our

ideal of morality. First of all, there is the indiscriminately direct-

ed love of mankind (humanity) and pity, and then comes the

fact, that the majority of the so-called 'acts of charity* would

343

have to be stripped of their attribute of virtue and left for what

in reality they are, merely actions which in the life of man must

be considered as selfunderstood. Namely the duty-to-life expects

everyone to be ready to do to his fellowman what he himself

would be done by in a similar case so that there would remain

very few, of which it could be said, issued from the wish-to-bc-

good. When we come to treat the morals-of-life, it will be noted

that "Altruism" or the selfsacrifice for others, practised indis-

criminately, is just as immoral as "Egoism", or the indiscrimin-

ate practice of self-interest is. Indeed, our standard-of-morals

expects, even in the practice of charity, a plenitude of inward

depth and profundity to enable man to understand properly

how to measure his actions according to the divine-wishes and

which, by his own free decision, in each and every sundry case

he will continue to do, until in the end, the correctness of his

judgement, as to what is moral and what is not, will have be-

come, a habit which has gained the quality of reflexibility. After

which, in the spirit of sureness he is now possessed of, he will

very likely be tempted to say to others: "Just tell me for whom

you are sacrificing yourself, and I will tell you, who you are."

But as mankind, in general, have grown so callous in their

feelings towards God, it is no wonder we are pleased to find

(amidst the spirit of selfishness which is everywhere rampant)

any traces at all of pity and diarity no matter of what moral

kind they are, although this should not be allowed to drive us

to the abuse of ignoring the dangers, for the sake of this fact

which are hidden in the prevailing moral estimations. When we

think of the towering grace man is capable of, the dwarf surely

can never serve him as a pattern!

Besides the duty-to-life, as well as the divine emotions of

pity etc., there are other conceptions, of a most peculiar kind

which also dominate the struggle-for-existence in the life of man.

These are manifested in the so-called 'morals of society*. These

344

however, are in very light touch with God. Instead of giving

support to the divine-wishes, they often oppose them. These

'morals of society* are governed by the rules of respectability

which sprang, originally, from a twofold noble source entirely

harmonising with God. The one is proud self-command together

with the gentle consideration of others, and the other is the

Wish-to-Beauty. These demand men to practice selfcontrol in

order not to give way to any outbreaks of their instincts or

affectations, as moderation in all things gives equilibrium to a

man's behaviour which is least irritating to those around him.

Through such behaviour, beauty of mien is gained; a fulfilment of

the Wish-to-Beauty. Politeness is demanded when wishes of any

kind are expressed or knowledge of the wishes of another are

desired. Man's dress and the surounding in which he lives must

comform also to the Wish-to-Beauty. Now, all these endeavours

are most certainly important. The mistake is, that the value put

on them is tremendously overrated so that, in the endeavour to

fulfil the demands owed to good-society , the vital ones are forgot-

ten. And yet this selfsame good society is not abashed at immoral-

ity of the most formidable kind. For instance, what a mockery

of the Wish-to-Truth it is, when men become so frivolous as to say,

that nothing really is shocking as long as the outward appear-

ances are kept up. What does it matter whatever happens in the

intimacy of the family-circle, as long as it doesn't leak out to

cause 'scandal'. To be in control of oneself in public is much

more important than the control of ones passions in private! In

private, even blasphemy is tolerated, that means to say, the

participation of the Life-in-God is degraded, in that it becomes

a part which has to be played in the round of social duties, a

'social call* paid on God, so to speak. Moreover, ladies and

gentlemen remain members of the church in all good conscious-

ness and remain so all their lives, confessing to it without a single

blush of shame, although, in reality they are only " Christ ians-

345

in-name" and nothing more, in that the belief they profess to

cherish has lost for them all its powers of Conviction.

Now, observe again for the second time, how the moral prin-

ciples which men have thought good to follow in the benefit of

the general struggle- for-existence have, except for the 'virtues

of society', nothing at all in common with the nature (Wesen)

of the divine. This explains for the gulf which has arisen to se-

parate the works of a divine-nature from the general struggle-

for-existence. The latter became gradually modelled on certain

lines in the existence of the higher developed folks of culture

and at first sight commands respect, although in reality it is

antagonistic to the vital interests of 'culture'. Nevertheless, every-

thing was thrown together and was called 'civilisation', no

matter how erroneous the indication was. "Civilisation" began

with the evolution of reason, when the first implements were

being made to facilitate the struggle-for-life, and the duty-to-

life began to take definite form. Therefore 'civilisation' does not

mean decayed culture (as Spengler has it); civilisation and cul-

ture are two utterly different things and have always been so

right from the beginning of time. For "Culture" indicates, that

God has become visible to the human-eye which is so, when the

labours of artists or researchers or words or emotions manifest

something of the divine-nature. On account of the great develop-

ment which reason has undergone and its consequent arrog-

ance, civilisation oversteps its grounds, threatening, in doing

so, to suppress the fruits of culture which alas! eventually can

lead to its complete elimination.

Contrary to all the other standards of morals which have

played their part in the history of mankind during the past,

ours bring culture and civilisation to agree with each other. The

struggle-for-life is given its proper due, not that it is let to go

its own way, unconcerned of divine-wishes and divine meaning

of man's life, however; on the contrary, everything concerning

34*

the struggle-for-a-living is subjected to the guidance of the di-

vine wishes, thus making it possible for man to act well, that is

to say, in accordance with the divine-wishes. In this redeeming

process however, we fear little would remain of that state which

we are wont to call to-day 'civilisation*.

347

Comments

Post a Comment