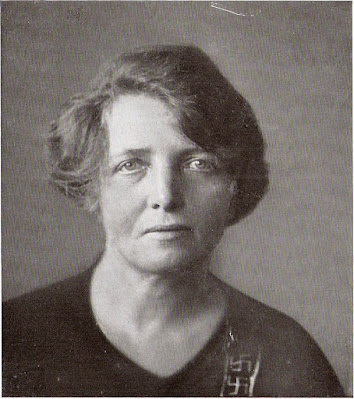

The Morals of the Struggle-for-Life - Part 6 - Book Review - Triumph of the Immortal Will by Mathilde Ludendorff

Summary of Mathilde Ludendorff’s Chapter: "The Morals of the Struggle-for-Life"

- Conflict Overview

- The struggle-for-life, driven by utility-based vital desires, clashes with the purposeless divine wishes, creating a profound gulf. Misconceptions of God, fueled by reason’s half-knowledge, deepen this divide, thwarting the Immortal-Will’s redemption through consciousness.

- Animal Existence as Baseline

- Higher animals live for survival, alternating between torment (hunger, fear) and rare peace, lacking memory of past or future. Their stateless dignity contrasts with humans’ restless complexity, though state-bound animals (e.g., ants) sacrifice peace for collective protection, mirroring some human lives.

- Human Degeneration

- Unlike animals, humans inherit reason, amplifying vital desires (e.g., greed) and memory of suffering, yet often stagnate in hatred and indifference. This degeneration, not just struggle, opposes divine potential, though God-living individuals overcome it with spiritual vitality.

- Divine Transformation of Hate

- Animals exhibit hate only in immediate danger, reverting to indifference, while humans’ persistent hate, rooted in the Immortal-Will, paralyzes divine wishes like goodness and truth. God-living transforms hate into a directed force harmonious with divine aims, not its eradication as in Buddhist/Krishnaite creeds.

- Sublimation of Vital Instincts

- God-living neither denies nor mortifies instincts like hunger or sexuality (contra asceticism) but interpenetrates or suspends them. During divine states (e.g., artistic creation), these fade, reasserting post-experience without shame, aligning with life’s sanctity as a prerequisite for God-living.

- Beauty Amid Ugliness

- Urban life’s ugliness stifles the Wish-to-Beauty, but God-living counters this via imagination, rendering men-of-genius oblivious to it, akin to animals ignoring the irrelevant. Beauty, less targeted by hate, thrives under divine influence, bridging struggle and the beyond.

- Reason’s Dual Role

- Reason’s laws and mastery of nature ease survival, unintentionally aiding divine wishes (e.g., through charity, justice), yet population growth and degeneration harden the struggle, undermining these bridges. Its errors (e.g., timing life mechanically) further alienate God-living.

- Historical Bridges

- Early communal laws (e.g., goods for blood) and charity bridged struggle and divinity, valuing life and fostering peace. Degenerate creeds (e.g., Krishna, Christian) distorted this by universalizing charity, neglecting folk purity and mixing divine wishes with legal duties.

- Spiritualization Process

- God-living resolves the gulf through: (1) associating instincts with divine wishes (e.g., spiritualized minne), (2) suspending disruptive desires during divine states, and (3) empowering divine wishes to dominate. Errors and degeneration historically obstructed this natural unification.

- Moral Implications

- True morals reject ascetic denial or utility-driven distortions, embracing vitality’s sanctity. God-living integrates struggle and divinity, offering redemption within life, not through post-death myths or materialist reductionism.

- Vital vs. Divine Conflict: Struggle-for-life opposes God-living, deepened by reason’s errors.

- Animal Contrast: Simplicity vs. human complexity highlights degeneration’s role.

- Divine Sublimation: Instincts transform, not vanish, under God’s influence.

- Reason’s Ambiguity: Aids survival but often hinders divinity.

- Redemption in Life: God-living bridges the gulf, fulfilling the Immortal-Will pre-death.

The Morals of the Struggle-for-Life

The struggle-for-life, the vital desires, thirst, hunger, sexual-

ity, together with the misconception and misinterpretation of

God, (caused by reason's half-knowledge mingled with error)

have worked such havoc in the soul of man, as to make the keen

observer lose all hope of perfection ever being achieved on earth.

For alas! The divine potencies in man he sees everywhere

stunted.

Now we might be led to think that the fallacies, caused by

reason's half-knowledge, the evil done through the vital-desires,

greed especially for money, (still unborn in the animal-kingdom)

were the only causes which induced the struggle-for-existence

to feel hostile to God. Deeper thought shows how erroneous this

assumption is, for a yawning gulf must exist between a struggle-

for-existence which is ruled by principles-of-utility and wishes

of a divine kind which are distinguished by exactly the absence

of such like principles. Thus, then, the gulf can appear to be

almost unsurmountable. There is a tragic air about the fact, that

the redemption of the Immortal- Will which finally came to

pass in the awakening of the divine-wishes to consciousness

should have created another gulf, graver than the one already

existing between the Immortal-Will and natural-death. The

significance, it bears, seems all the more obvious, in as much as,

contrary to the adherents of religions which teach of a heaven,

we are fully aware how necessarily important our existence,

that ends with our death, is, in respect to the realisation of our

Immortal-life.

In order to realise properly what this apparently unsur-

mountable gulf means we should, do well to make an observ-

ation of a certain existence first which is totally free from the

direct workings of either God or degeneration. For this purpose,

the life of the higher animals are best to choose, as these are

next to us.

When the young animal leaves the care of its mother to enter

independently into the general struggle-for-life, many things in

its surroundings crowd in upon it. Already it has learned to

know the ones which are its bitter enemies; these fill the young

animal with fear. Others, it has found out, are of no importance

in its life and therefore it takes no notice of them. The rest it

mistrusts, being still unaware of the nature they are made of.

Warding-off danger and the search for food are the two occup-

ations which fill up its life. It is roused out of its mood of

peace through torments of hunger which were sent by the self-

preservation-Will within it. The tortures it generally has to

suffer are so out of proportion to the fleeting moments of

pleasure which it is allowed to enjoy, that it might seem as if

something like a curse hovers over its existence. It is well to

know first that the beast is priviledged to sink into the state

of blessed oblivion, or else the 'patience* with which it suffers

its joyless and burdensome fate might appear to be almost

incredible. It lives merely in the present. The past it cannot

remember consciously, and the future, with its looming pains

and fears, is beyond its power to anticipate. Much peace has

been granted to the beast, which lends to its behaviour a charac-

ter of stateliness, especially when it is compared to the hastiness

and restlessness of man. It will never be induced to struggle

for anything more than for the bare necessities of its existence

and consequently, as soon as these are secured, it sinks back

again into the lethargical state it is accustomed to, where no

emotions of joy or pain can touch it, so that we think of the

298

beast then as being in the same condition as human beings are

when these feel 'comfortable*. The very young animal will

manifest more feelings than those of comfort. It shows how

glad it is to be alive when times are peaceful. It is up and doing

things without the necessity to earn its living forcing its actions.

It springs and jumps about in play, 'free from any care*. Just

like the human child, it loves teasing its companions; it is

enjoying life!

There are cases when the adult-animal is also capable of

enjoying life. The domesticated-animals give clear witness to

this fact. The dog, especially in that it has been spared the

struggles for its own existence through the care of its master,

will show signs of undiluted joy. The rest of the animals, how-

ever, which have to fight for themselves, are quickly sobered

and at a very early period lose all desire for play. In old age

the lethargical state, characteristic of the beasts, is uninterrupted,

save for outbreaks of bad temper or the excitement of combat.

This gradual descent from an overflowing joy to sobriety and

from this to morbidity and bad temper are signs well known

to us. It is the scale of emotions generally prevailing as the

ages change, not only in the animal kingdom but among human-

kind too. It strikes all those individuals, who, in having been

too taken up with superficial cares, have remained ignorant of

God's life. This does not imply however that the struggle-for-

existence is alone responsible for the descent of the emotional-

life, for, curiously enough, it is found to exist in individuals

who are not obliged to fight for their own living. In fact, it is

very clearly exhibited in actually lazy people who let others

work for them. Old age is the chief cause of it. In other words

the gradual loss of life's power or 'vitality' of the soma-cells

which have been doomed to age and die. Therefore it comes

natural to all beasts and men, save those men who have cultivated

299

God within themselves. The decrease of vitality, in the somatical

sense, is overcome by an increase of the powers of genius.

Thus then, the life of the individual animal passes in alter-

nate change; from states of frequent work and torments to the

rarer times of peace and rest. Yet this is a fate which indeed

can be called a 'happy* one, when compared to the existence of

some other kind of animals which, to avoid danger, have united

together in a kind of state-community, as for instance the ants

dave done. Their lives are utterly bare of any peace or rest at

all, they are like the organs of the multicelled-beings. For

instance, the heart keeps on pumping without the slightest

interruption from the first until the last minute of life. In like

manner animals, such as the ants, start working in service for

the community and then never stop until they die. The greatest

struggle-for-life which might happen to a single animal,

accustomed to danger, is nothing compared to the hardship and

monotony of those animals ruled by a state. In having con-

gregated, they have found better protection. Unity has made

them strong, so much so, that they have become the feared enemy

of animals, they could never risk to encounter alone. But for

the protection which this community affords them they were

obliged to sacrifice the sole delights which could ever be theirs;

peace and independence! If they could but know that inevitable

death one day, of a certainty, will destroy the grand edifice,

they have taken such trouble to build, as well as themselves;

what would happen, we wonder? Would they still continue as

before to labour at such a restless pace? Incredible though it

be; there are numbers of individuals among mankind who live

no worthier than the hasty ants. In fact they persist in this way

of living, although they know quite well about death and what

all their troubles are really worth. Notwithstanding, they have

not the slightest ambition to change their mode of life for the

better. Not even that mode of life attracts them which at least

300

the animal, living singly, enjoys: The existence which falls into

a state of peace as soon as ever the bare necessities for a living

have been acquired!

Although life in the animal-kingdom has not had to suffer

from the effects of degeneration, it is crystal clear that it runs,

nevertheless, in the opposite direction to the divine-wishes ot

God, (for these are spaceless, timeless and without purpose.)

A deep gulf yawns between the nature of the vital-desires and

the divine-wishes of the soul. But might there not be the

possibility of spanning bridges over the deep gulf by means of

feeling which might have a divine nature?

Wherever we look in the emotional-world of the animal we

see hate underlying all the feelings they exhibit towards their

surroundings. On the occasion of a superficial observation this

fact is hidden, because of the incapability of the animal-mind

to remember things. It is not on the level of a man's state of

consciousness. The animal, in being incapable of retaining

experiences in its memory, will express the feeling of hate only,

when it is actually capable of sensing it and that is, practically,

at the time of danger and only while this actually lasts. Hence,

as soon as danger has passed, it falls back again into its habitual

state of indifference. But the voice of the Immortal-Will, within

the animal, continually admonishes it to hate everything, dead

or alive, which threatens its life and never will the Immortal-Will

cease in this demand! This is a fact, the vital importance, of

which every living thing tells us of and which we must indelibly

imprint on our minds, because the nonknowledge of evolution

and its laws has done already such infinite harm to man. It goes

without saying, of-course, that in those men, whose Immortal-

Will sublimated in longing for God-Life, hate shows trans-

formation similar to the spiritualisation of the Immortal-Will.

(We shall come back again to this theme.)

The sadly monotonous state of emotions which the animal

301

exhibits to the world around it is made up of hate and indiffer-

ence. Occasionally, however, this is interrupted by the waves

of sexual-heat which make themselves felt and which induce the

animal to approach, accordingly, the other of its own kind. But

as soon as its sexual-sensation has been gratified, it falls back

again into its old monotony. The sensations, experienced in

connection with its young, are of a deeper and more lasting

kind. The higher the class is to which the animal belongs, the

more helpless it is after birth, the stronger grows the mother-

instinct together with the desire to tender and make sacrifices

for the young. This is the fount of all the deep mother love. But

even this instinct fades away into indifference as soon as the

young have gained the state of independence. Finally, we can

observe how the animals congregate together in herds or flocks,

or live in matrimony, like birds do, thus manifesting an emotion

the kind of which can be described as having 'grown used to

each other' which strongly puts us in mind of the family relat-

ionship of man. In gloomy world of brute emotions, there

is not yet the faintest shimmer of the divinity but it is there,

nevertheless, only slumbering. The behaviour of the higher kind

of animals, when they come in contact with man whose soul

exists in the most awakened state of all, give ample witness to

this fact. Already we have heard of the awakened state of

conscience which the dog will exhibit and also the sentiments of

tender attachment it develops, when longer in the company of

man. Sentiments, which, in respect to strength and permanency,

it is utterly incapable of exhibiting for its own kind. If this

means, that the influence which the mind of man exercises over

the dog and the care he takes for its welfare is the cause of the

divinity awakening which manifests itself then in sentiments

and actions, it also means, that the divinity before that was in

a state of slumber.

Observe then, how this daily intercourse with man has

302

produced a creature which is neither man nor animal. Here we

seem to have to do with an 'anachronistical' (if we may so call

it) awakening of the divinity in respect to the sentiments and

actions of the animal towards its master; the one who has proved

to be its friend in the struggle-for-life. And yet, every time

the domesticated animal is obliged to play the part of a struggler-

for-existence which sometimes happens in spite of its priviledged

position; the pitiful alternative between hatred and indifference,

manifest in the state of its emotions, steps again into its rights.

It is interesting to watch the divine glance spring into the eyes

of an animal when it is acting from feelings of attachment,

forgetting sometimes, when it does so, its own instinct of self-

preservation; and then compare the virtuous nature of this

glance to the glance which is habitual in the eyes of all such

men in whom the divinity is dead. In having given themselves

up to the sole endeavours of earning a living, while enlisting as

well in the petty service of mere utility, such individuals have

become animalised in an anachronistical manner.

Already we have been fully satisfied that the divine feature,

called truth, exists everywhere, albeit unconsciously, in the

animal-kingdom. All the animals 'ring true* in that their out-

ward behaviour accords with the motives for the deed. How-

ever, there is a grave fact we may not overlook here and that

is; the higher the animal-mind (understanding) has become

developed, the more easily do those characteristics, called

cunning and slyness, make their appearance in the heat of the

combat which aim at deceiving the enemy as to the motives

which underlies the deed. The evils of cunning and slyness, how-

ever, are redeemed in the animal from the fact that they are

applied only in cases of emergency, i. e. when the life-interests

of the animal are in danger, in the strict sense of the word.

Therefore the animal's habit of cunning and slyness are in no

ways identical with the hypocricy and lies which distort the

303

life of human-kind. Nevertheless it makes us feel grave to think

that the impulse to use trickery in the struggle-for-life was

inherent in the breast of man almost before the divinity in man

began to awaken; it was the characteristic, he was already in

possession of as representing a piece of property which had

been bequeathed to him from the animal-kingdom. Observe

now the make up of the inheritence received from the animal.

Instead of the Wish-to-Goodness and Beauty there is the sole

interest in utility. In place of charity, hatred towards every-

thing which threatens its life, and in place of the Wish-to-Truth

the use of strategem, when danger of death is near.

The majority of mankind indeed live similar lives. Nothing

varies the state of their emotions which change alternately from

hatred to indifference. When they have to work, they are

animated with the thought of the profit it brings, otherwise they

prefer being indolent. Passing sexual-intercourse makes up the

rest. Yet they are without the benefits which the animal enjoys,

in that it is oblivious of the past and suspects nothing of the

future, for the awakening of reason has changed the whole

course of man's life. Reason has built a bridge of errors in order

to span the gulf between natural death and the Immortal- Will.

In similar manner it has tried to span the gulf between the

demands of the struggle-for-life and the divine-wishes existing

in the soul of man, but that bridge likewise was built of errors.

Just as the course of development found its way to spiritu-

alisation, in spite of all the deviations reason seemed obliged to

make, and the yawning gap disappeared, the divinity in man

subjected vital-desires to divine-wishes, so that unity came to

pass.

In very early times, already, men were fully conscious of the

fact that the vital-desires strongly clashed with the divine-ones.

The contrariness and antagonism which had sprung up between

the two began to appear almost insurmountable. To prevent this

304

state continuing men thought out means to overcome the diffi-

culty, but these have proved since to have been of a very

erroneous and uncouth kind. One of these primitive methods

still exists to-day and might be called the worst of its kind.

It is the habit men have of wrapping up the divine-trends into

space, time and purpose. Having thus been stripped of their

divine nature, it was an easy matter to bring about a union. (We

have already treated these attempts and the results which

followed). The second method which cropped up with the same

regularity as the first in all the religious teachings of the past is

just as erroneous, because of the awful ignorance which is

revealed concerning the meaning of life, the law of life, as well

as the true nature of God, although a greater spirit of respect

is manifested towards the divine-wishes. It teaches that, as vital

desires are contrary to God's Will, the only escape from them

is through the practice of asceticism and the denial of the world.

Consequently the monk's cell was resorted to, where, in hours

of prayer, sin could be overcome. Undoubtedly this was a life

which was dedicated to God, but undertaken in such a onesided

way and in utter ignorance of the fact that the vital-desires

are capable of being sublimated and united to the divine-wishes.

While the asceticism of the monk considered sexuality to be

the worst sin against God but surrendered itself willingly to

the temptations which the enjoyment of eating and drinking

offered; another kind of religious-ideal considered fasting to be

higher than chastity in the eyes of God so that in this case the

food taken was not only limited to the smallest quantities but

also to certain particular kinds. It was thought that such rules

would help to lead a man to God: In Theosophical and Antro-

posophical-circles a kind of divine cookery book has made its

appearance according to the recipes of which a state of perfect-

ion can be concocted. The origin of these fallacies are to be

found in the doctrines of Buddha and Krishna which cropped up

305

at the time of the decline of the Indian race. Christianity

adopted very many of those creeds, but the errors, we have just

mentioned, are not preached in the gospels in this way exactly,

although the surrendering of one's possessions is claimed to be

a good way to gain salvation. The Indian exhibits a greater

independence of fate than the Christian does. The Indians

sought to overcome the conflict, existing between existence and

God, in that they strove for an attitude of greater indifference

to fate. Their myth of rebirth aided them in their efforts. It

admonished them to disdain struggling for life also for life's

joys and sorrows should they wish to gain that state of inward

peace essential for the sinking into contemplation which is the

participation in divine life. Notwithstanding the fact, that the

Indians were a folk of deep philosophical-trend, their religion,

like all other religions which teach of a life in another world,

lacked the drive and potency to genuine divine contemplation.

The art of Yoga which they were in the habit of teaching gives

ample witness to this fact. This contains religious-practices

which are supposed to help man to participate in the life of

God, inspite of all the impediments which lie in the way.

According to the truth which has been revealed to us, we know

that the possibility to partake in the life of God is given to us

in this life only. It is the very gravity of this thought which

animates us, and as we know by experience what the real nature

of God is there is something comic about laying down fast rules

wherewith to obtain the life in the beyond, especially when the

rules practised are those of auto-suggestion and the results which

follow mistaken for God-living (Gotterleben). Moreover we are

amazed at the doctrines which laud poverty, chastity and self-

denial, as being the adequate means in overcoming the conflict

which separates the struggle-for-life from God-living.

Verily, God-living (Gotterleben) strikes out on quite a differ-

ent path. In its endeavours to solve the problem it does not

306

allow itself to be roughly dragged into the daily routine nor

does it flee the world. On the contrary, in its own sublime way

it interpenetrates all vital-desires in subjecting them to the

divine-Will.

At the time, when mankind began to live in communities, he

sought for revenge for murder the keener his memory grow.

The impressions, however, which the results of the continual

chain of revenge for homicide left on his brain were so fatal in

the end, as to make him seek new ways to make up for the

taking of life. Goods and chattels were demanded instead of

life. Here for the first time the conception was born that guilt

should be atoned for. Later this idea, in the sacrifices of those

races who distinguished themselves by their fear of demons,

gained in significance. But not only that, goods and chattels

became suddenly of great value, in as much as they could be

exchanged for the very life of a man. As a consequence the

individual life of man also gained in value, in as much as by

such means it could more often be saved than heretofore. As

a result of this reasoning the beginnings of a foundation to

laws-of-the-land were laid (I repeat laws which were born of

reason) and simultaneously, although unintentionally, a bridge

leading to God was built. For through the surrender of goods

and chattels, instead of strife, peace and goodwill appeared on

earth which were the essentialities to progress.

The suffering, memory kept alive which had been caused to

some in the community through the selfishness of others, made

reason think it good to extend the hand of the law over all the

other ranges belonging to the protection of life and good with

the motto on her shield: Do to others as you would be done

by. At the same time, as if to balance this, there existed an

inherent selfpreservation instinct subconscious in the breats of

man (who at that time still lived in the purity of race) which

was identical with the instinct to keep the kind going inherent

307

20*

in the animal. This instinct is clearly manifested when the

animal cares for its young or puts up a tenacious fight for its

own life, or as in the case of the ants and bees (the state-builders)

the intense service each one makes for the good of the whole.

The dire knowledge what foolish behaviour man is capable of,

resulting in such infinite harm to himself, his family and his

folk, in that freedom instead of compulsory force accompanies

his selfpreservation instinct, made the wisest and best think it

proper to lay down fast rules to make up for the absence of

force in this instinct. Though these laws are born of reason and

serve practical purposes, yet the divine in man was now actually

given the first royal chance of exfoliating; in other words, the

conflict, existing between the divine and vital-trend in man, was

overcome for the first time, although unintentionally on the

part of man himself, for he could not have been aware of the

effects which would follow from all this.

Incomparably more essential in bringing about the friendly

relationship between the two worlds (here and beyond) was the

power of the divine, as it grew conscious-in-feeling together

with the support it received from the doctrine of charity which

for its part had been prompted through the natural desire man

felt to help his fellowmen. Such deeds were called the 'social

virtues' and became, eventually, the means of building an expan-

sive bridge connecting the struggle-for-life with God. The fatal

results which issued later to the general detereoration of so

many folks of the earth came about when charity was being

practised without any discrimination and the duties to family

and folk were neglected as a consequence. This evil had its

origin when the Buddha and Krishna creeds of a coming

'redeemer* found acceptance in the Indian folk after it had

become degenerated, and when later the Jewish Apostles added

their creed of hate towards others who did not profess the same

creed; this evil, in that it was a race destroying element, grew

308

even worse. Thus then, the bridge, leading from the struggle-

for-life to the realms of God which had promised such success,

had become now also the means of the folks' destruction. In the

one great virtue, called charity, (humanity) all the other

opportunities which the wish-to-goodness offered were over-

looked, so that it came to pass that genius came but second to

the demands which the practice of this virtue made on him.

More even, as the consequence of this ignorance the divine

wishes got all mixed up with the duties owed to the common-

law (laws of the land). And this error happens to be the worst

which still exists in the morals of today. Yet, despite this grave

error, the bridge, leading from struggle-for-life to God, still

holds, for indeed the common-laws and charity have bestowed

a great blessing on mankind.

Another great aid was the progress in the development of reason

itself. Although reason is capable of erring and in having often

done so caused the struggle-for-life to become so degenerated

and full of unnecessary hardships; through reason, nevertheless,

the struggle for the bare necessities of life, that is, the life we

think of as being contrary to the life led in the light of the

divine-wishes, has been greatly improved. To understand what

this means, we have but to bear in mind the immeasurable

benefits to mankind which the cognising potencies and insight

of man's reason have brought; for instance every time he was

able to perceive the prime-cause amidst the cosmical happen-

ings. By virtue of his reason's potencies man has become the

master of the forces of nature instead of their slave: What once

was of danger man has turned into his service, something

which the animal mind was incapable of doing. Hence, the

struggle-for-existence has been made comparatively easy for a

great number of individuals provided of course, that the

vississitudes of war and catastrophes of nature have been spared

them. From this might be expected, that less stood in the way

309

of the fulfilment of the divine-wishes, than in those far-off

centuries when the forces of nature had not been mastered yet.

But it is not so, for the steady increase of population and the

evil effects which the state of degeneration leaves behind it has

rendered the struggle-for-existence even more difficult than it

ever was, so that it goes almost without saying, that the

marvellous bridge, crossing from here to the beyond, has been

laid almost barren through reason's evil concoctions.

Yet the influence of the trends of God's Will, inherent in the

breast of man, have caused the trend of his animal emotions

and instincts to be so closely interpenetrated with these, that one

might well speak of a 'divine' transformation. They have

formed another bridge, more beneficial and of more importance

which man could use if he desired to enter the realms beyond.

As we have already observed, the fundamental sensation of

all vitality was hatred. It was the sole sentiment which was

capable of arousing the living-being out of its habitual lethargy

and was directed against everything, without exception, which

might threaten in any way its own life. Now, as man, unlike the

animal, cannot forget the past, the feeling of hate, in particular,

has proved to be the worst of all God's enemies. It is apt to

paralyse terribly the feelings of charity; in so many cases it has

suffocated altogether the wish-to-goodness, and it has rather seen

lies than the wish-to-truth triumphant. Alone the wish-to-beauty

it leaves unattacked. For this reason the sense of beauty has had

a better chance to develop in the cultural folks than the other

divine- wishes have. We are not surprised, therefore, that Buddha

and Krishna, in face of this awful danger to God-living, felt

obliged to create those world-religions of humanity which

chiefly contained doctrines preaching the resignation of hate.

In those creeds man was admonished to quench the feeling

of hate within him altogether. He was told that if he practised

310

the virtue of charity, he could even turn his hate into love. What

a fatally absurd idea this was! If a man should ever succeed in

rooting out his sentiments of hate, he would have first to

extirpate his own innate Immortal- Will, for, as we have clearly

perceived hate has its origin in the Immortal-Will of man,

which, by the very law of its being, must flare up into hate in

order to give the signal that life is in danger. Thus then, the

results of the exhortation to resign hatred in reality looked like

this: In many ways it appeared as if hatred had been successfully

overcome, in reality however it still worked disaster in the soul

of man. It is a pity we must refrain here from discussing the

sublime way of redemption, where, under the divine influence,

hate can be successfully transformed so as to be fit even for the

service of God. We should be going too far into the range of

our morals. But one thing we should like to mention here, and

that is, if the sentiments of hate are put under the guidance of

the divine- Will, the deep gap which it usually makes will be

easily bridged over, for harmony instead of discord will reign

with God then.

The vital-instincts, inherited from the animal, work also in

a contrary direction to God. But here also, the divine-wishes

are able to overcome the conflict in their own sublime way, they

can either interpenetrate the vital-wishes or loosen them from

their bondage. Both ways are far superior in its kind to the

petty endeavours springing from the reason which the Indians

and Christians put forth when they preach of the resignation of

the sexual and food-instincts. God demands neither chastity nor

fasting from mankind. On the contrary, potential life in the

individual as well as in the race is holy and significant to God,

for the simple reason that the life in the realms beyond can be

assured to man only as long as he lives. Therefore God respects

all sane vitality in allowing all the conditions essential to it.

And when the vital-instincts threaten to become stumbling-

blocks which hinder man's partaking in the divine-life, it is

again the divine influence which steps in and liberates man from

his vital-instincts altogether. For instance, a creative artist can

go on for days without almost any food when he is particularly

taken up with his artistic production. Being then in the realms

beyond, hunger and thirst are practically not felt. Days and

nights will be passed in utter disregards of the wants of the

body. But as soon as the state of genial production has passed

over, the body demands its rights again. Then the artist, not

like those hypocrites who believe a good appetite to be some-

thing unholy, will satisfy the wants of his body with right good

will. In this way, then, God-living is enabled to escape with

case from the bondage of the strict rythmical beat of the body's

want of food and its satisfaction, when its subjection to these

would mean a hindrance to the realisation of the divine Will,

namely that time a man spends in the life-beyond. A sane person

will always refrain from exaggeration, even in this respect, in

the sure knowlegde that the satisfaction of the natural demands

of the body is essential in order to lead a healthy life, for earthly

existence is the prime essential to the living of the Life-Immortal.

In this endeavour, therefore, the impulse for food should neither

be mortified nor unnecessarily restrained. What really matters is,

that it should get rid of that trait which is so awfully hostile

to God and which makes it so difficult for a man to live his

life in God, in those realms where time is not. We are thinking

of the antigodlike habit man has of strictly timing all his

experiences with the slavelike regularity of the machine! Un-

fortunately man succumbs to this fault only too readily, thus

making it so difficult for himself to bring the daily struggle-for-

existence to harmonise with God. Moreover all the numerous

inventions of his own reason's making appear to fetter rather

than free him from the enslavery which the living of his life

means when he divides it strictly according to time. We shall

treat this again.

There is another feeling of pain and discomfort, from which

a like divine escape is undertaken when it tends to act as an

impediment to man in his participation of God, and that is

the feeling of pain caused from illness. These arc practically

not felt at all, when the patient lives God. In fact, it is amazing

to what extent the insensitiveness to pain will grow, provided

the divinity in a man was been keenly developed. (Of course

it must be clearly understood that by this we do not mean

anything which is connected with the painless zones of hysterical

individuals.) Nor must we think that merely distraction is

required, should this state of utter insensitiveness to pain be

gained. Incidently, Christian-Science has occupied itself with

this problem with the result, that the truth has suffered complete

misinterpretation. This singular behaviour towards pain which

a patient will manifest during illness has led to the belief in the

fallacy, that pain is one of the 'corrective means of the deithy',

sent to man for his salvation. The different conditions of the

patients rest chiefly on the nature of his liberation from pain.

Is it of a divine nature, this will be reflected in the patient's

whole behaviour; while the mind of the one concentrates itself

wholly on the diseased part, the other, it will be observed, will

give hardly the sufficient attention which even the doctor might

think was due to his illness. On the contrary, if the endeavours

to gain a living left him little leisure while he was able to get

about, the sick-room will be dear to him in that the chance is

given him to partake of God in peace. And it is this divine peace

only which is able to obliviate pain. In the keen occupations of

the practicalities of life or in the passion of the chase after

avarice or ambition men will be made to forget their pains too,

but never are these distractions appropriate like the workings

of the divinity are in making men so divinely insensitive to

3*3

pain. But, of course, whereever the intensity of the pain is

greater than the attained state of insensitiveness, these will

prevail, calling man's attention to them imperatively.

Now that we have finished demonstrating the independence

of physical defects which Godliving manifests, ve must turn

to denounce as error the statement that bodilj health and

power are a hindrance to the development of the di/inity innate

in man; this is most certainly not the case. On the contrary,

complete health of, all the soma-cells is of vital importance in

order to achieve that state of keener consciousness which facil-

itates the endeavours of a man to live according to the divine-

wishes of God's Will. If, however, the subjection of the vital-

instincts to the divine-wishes has been neglected and by reason

of this fact have remained still at the animal-stage and as such

are contrary to God, they will be more capable of hindering the

development of the divine- wishes, than the weakened instincts

in the case of the bodily infirmed. As the religious moral-creeds

exercise such an extraordinary influence over the majority of

mankind, few have been really able to subject their bodily-

desires to the Will of God, and as a consequence it has become

almost essential for a man to have weakly developed passions,

should he be able to do justice to the Will of God.

This fact brings us round to face sexuality as being opposed

to God. How can this be put right? During God-Living, the

influence of God is so strong that sexual-passion disappears of

itself, so that its opposing effect is hardly obvious. However,

the best way to overcome the opposition is to associate the

sexual-will to the divine-wishes. The more this takes place, the

greater will it be dependent on the fact in how far the divine-

wishes are satisfied or dissatisfied. When finally sexual-will and

divine-wishes have become inseparable, the conflict between the

two Will have disappeared altogether, if but from the fact that

the desire for any sexual-communion would disappear, as soon

as it threatened to stand in the way towards God, without a

man feeling anything extraordinary about the matter. In effect,

sexual-passion, provided it is held completely under the sway of

its association with the divine, can be raised to that rank which

we shall henceforth call spiritualised minne. Once in this rank,

it becomes the most powerful aid in the fulfilment of the divine-

wishes which before might have slumbered. Then, not only the

experience of joy becomes divine, but the experience of suffering

also.

When we come to demonstrate our morals of minne, we shall

be obliged to concern ourselves, first with the fact, that man

has done very little towards supporting this relationship, in

that he has allowed the errors, caused by his reason's inefficiency

to perceive more than the half of truth to gain the upperhand

and in doing so has widened the gulf, already existing between

divine-wishes and sexuality.

We have already noted that among the divine-wishes, the

Wish-to-Beauty was less exposed to injurious hatred. It might

have had therefore a greater chance to exfoliate, had man, like

the animal, been permitted to live in closer connection with

nature, practising just the vital-demands (like the animal does)

which existence lays on him. As it is, the struggle-for-life has

been made so difficult in the noisy towns through the density

of which the rays of light and air can hardly ever pervade, that

the sense of beauty is under continual insult. Men, famished for

the want of beauty, are doomed to live all their lives in the most

ugly surroundings, making the divinity-in-perception more

opposed than it natural was towards that struggle in the general

chase for the practical. But here again God comes to man's aid!

Just as the influence of the divine was capable of releasing the

ties of time which threatened to make him the slave to his

bodily-instincts, in like manner the divine influence releases him

from the ties of space which bind him to ugliness. Sometimes

this happens through the power of imagination (phantasy) which

God makes use of. It becomes the magic wand which throws

the fairylike veil over the matter-of-fact, every day things,

making them appear to be things of actual beauty. Men, who

are full of God, will grow immune to an sting of ugliness until

at last they become simply oblivious of its existence. It puts

us in mind of the animal way of ignoring the objects around

it which happen to be neither of any use nor any harm to its

person. Therefore we conclude from this observation that men-

of-genius exhibit the same behaviour towards the ugliness which

they cannot escape from as the Greeks exhibited when they

nominated such inevitable ugliness, the 'non-existing' without

however their divine blindness being the cause for them to

neglect the necessary every day duties. In such men, on the other

hand, the divine-wish-to-beauty makes itself strongly felt.

When and whereever anything really beautiful strikes their eye,

their attention is keenly attracted, making them follow attent-

ively the thing of beauty with the same intense feeling as the

animals exhibit when anything useful or hostile makes its

appearance before them. Thus the men-of -genius, living in the

dirty ugliness of big cities, are saved from those moods of

melancholia which would inevitably befall them if their want

of beauty were not in some way or other redeemed.

Thus then, we are justified in summing up as follows. Man's

saviour is his God-living and not his reason, in as much as the

gulf which the awakening of reason created between the

struggle-for-life and the desires of man to live in realms beyond

was made to disappear again through the gradual process of

spiritualisation. The ways, this took, were, as we shall see, very

diverse. In the first place it transformed the inheritance which

the animal bequeathed to us, in that this was made to associate

itself closely to the divine-wishes (sexuality). Secondly any

disturbing feelings, such as hunger, thirst and those aroused at

316

the sight of ugliness, are periodically banned, so that the

participation of man in the life of God can happen undisturbed.

The third way, finally, which the process of spiritualisation

goes, is in the strengthening of the divine-wishes to power. This

way bears the most importance. Mankind might have been

spared much of the suffering which the conflicting desires of this

life and the life beyond still cause even today, had the process

of spiritualisation been allowed to go its own dear way. As

it is, succeeding generations were compelled to accept all the

errors and fruits of degeneration which belonged to their

ancestors, as well as the misconceptions of God which degraded

religions suggested. The process of civilisation (the knowledge

of the laws of nature and technical inventions) might have

become means of making the divine-wishes the superiors in

man's life; whereas the fact is, that the majority have to slave

and are abused for the sake of the enjoyment and lust of the

few (s. Each folk's own song to God).

Comments

Post a Comment