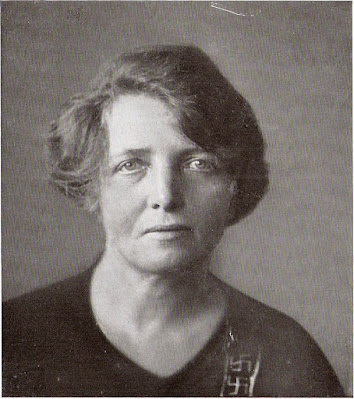

The Unicell and Immortality, + Notes (pt.3 Triumph of the Immortal Will by Mathilde Ludendorff)

Most of Mathilde Ludendorff's writings are in German and are rare,

please help me purchase them and translate them into English.

Donate: https://www.patreon.com/VincentBruno

Donate: https://www.patreon.com/VincentBruno

Notes from the chapter "The Unicell and Immortality" in Triumph of the Immortal Will by Mathilde Ludendorff (Chapter below):

- Science-Cognisance in its highest form is the knowledge all life came from a single cell called the unicell.

- Knowledge of physics and electricity removed ancient fears of thunder and the same will happen with fears of "powers of fate".

- Natural science shows god does not intrude but we are protected by the laws of nature, god cannot harm us in any supernatural way.

- But science did not serve the need for immortality, this through evolution was filled in living on through your children.

- Cells passed on to offspring in gamates are immortal? (Is that true?)

- Immortality is working for the best for our children.

- Christianity replaced love of ancestors and progeny with the will to preserve individual immortal souls (not group soul).

- But more than social work is needed, more than keeping the best for our descendants.

- The unicell is immortal since the primordial soup. (Is this true?)

- Cells have souls because they are "things themselves".

- Somatic cells die but germ cells are immortal, immortality is gained through passing on germ cells.

From The Book

The Triumph of the Immortal Will

By Mathilde Ludendorff

https://archive.org/stream/triumphoftheimmo029665mbp/triumphoftheimmo029665mbp_djvu.txt

The Unicell and Immortality

If ever there was a scientific Cognisance (Erkenntnis) which

was capacitated to shatter the mind of man and replenish is

with a new appreciation of its surroundings and the realities of

life, it certainly was the announcement that all life had once

evolved from the most primitive of beings, called a unicell.

When one comes to think of it, it seems almost miraculous that

within this infinitismally small body, invisible to the human eye

save when under the microscope, there lay such a power of

development as to cause, together with the aid it received from

its surroundings (the impetus danger gave in the struggle-for-

existence) the multifariousness of plant and animal-life which

we see before us. One of the most incredible facts in the history

of culture is this: As soon as this wonder became general good,

men became swayed in the fallacy they had solved the mystery

of life! There is no denying of -course that the struggle-for-

existence endowed the species with the more favourable var-

iety, and this facilitated reproduction; but does this fact really

suffice to explain the reason why that sleeping possibility un-

dertook a transformation as to cause the ascent of man amidst

struggles which continually increased?

Now, this has remained a mystery, but because all attempts

to solve this mystery from the mechanical point-of-view have

failed and always will fail, the truths gained from the Evol-

ution-Theory are no longer fated to remain the mere property

of an important branch of science as men up till now have be-

lieved; instead, their prerogative, to-day, is to inaugurate the

foundation to our new world- viewpoint (Weltanschauung) which

will soon bear conviction that it is a foundation far superior to

all those contained in any of the myths and religions. But not,

however, in that sense as has been understood up till now, for

the continuity of that progress of development to farther stages

over the line unicell-man we consider to be a creed which is ab-

solutely untenable. We are also opposed to the other conception

which hoick that the perpetuity of the species amply replaces

individual immortality. The religious myths always upheld the

personal immortality of man, and because this idea was kept

alive in the imagination of man it acted truly as an impetus to

all their moral endeavours. Yet we must admit that the preach-

ing of the immortality of the "species" as a gospel of truth

found its justification in one way also; namely it was prompted

by the same natural desire, the individual's immortality, which

was embodied already in the myth. All men are inspired with

a great longing for the immortal-state. By now the religious

myths would have lost all their significance had they not held

out to men the promise of immortal-life, for their second funct-

ion has lost all its significance. In earlier times its presence was

justified; the myth helped to appease the awful fear of men

when these were confronted with the elements which in those

earlier times could not be grasped with the human powers of

comprehension. Gradually, the myth was obliged to give up

this second function to natural-science which has succeeded in

a most marvellous way to appease the fear men were wont to

feel towards the wild powers of Nature. For instance, the fear

which men used to feel before the God-of Thunder who, in his

anger, annihilated them with flashes of lightning, has been

completely banished since men have discovered the principles

of physics. They know now that when electricity in the air

explodes it causes thunder and lightning. According to like

rules men can scare away the fear that takes hold of them when

158

confronted with the "powers-of-fate". The brighter the light of

science shone, the quicker did the fear of demons and the anxiety

for cult manifestation make its departure: Instead of the Will

of a personal God intruding itself onto the life of mankind,

tranquil lawfulness made its appearance. All of us, who have

gained any insight into nature and her laws, have experienced

how soothing the possession of clear knowledge is after the

anxieties felt at that time when we were still under the influence

of Christian-Thought. We forgot, however, in the first intoxi-

cation of our joy at this knowledge that this could not make

up to us for the loss of our belief in the individual-immortality.

A fervent and invigorating belief in a personal God who watched

over our welfare and to whom we could pray in times of need

was nothing compared to the peace of mind which the knowledge

of nature and her laws imparted. This belief was not able to

impart a like peace and tranquillity in the circumstances of life

unless the visible was disdained and even hated in the thought

that true life first commenced after death. And because of the

superiority which all those felt who had learned, to understand

and love nature, it comes natural that scientific cognisance

(Naturwissensdiaftliche Erkenntnis) became of its own virtue,

a new religion. Now religion is the consciously willed connection

with the 'Thing Itself as Kant has termed that something (self)

which animates all appearances (Erscheinung). As natural-science,

however, denies the existence of this 'Self, it follows, that it

is an error to call scientific truths religion. There is a great

difference between religion and a Godcognisance (Gotterkennt-

nis), which fully harmonises with science. Although religion

possesses a conscious desire to be inwardly connected with the

divine, it lacks the harmony with the standing facts of science

and responds to the ultimate questions of life quite irrespective

of the force of real facts; merely the wish-for-happiness or the

fear-of-pain come in question.

159

Thus then, science was most adequate in transforming the

fear of the demons into a state of tranquillity but it was incap-

able of satisfying the desire for immortality always burning in

the heart of man. When the Evolution-Theory revealed the fact

that the sex-cells bequeathed their heredity-substance to one ge-

neration after the other; as well as that these cells were potent-

ially immortal, it was at once assumed that the belief in the

perpetuity-of-the-species was a full substitute for the belief-in-

a-hereafter which the religious myths avowed. Even if facts

had been so hard as to dispel mercilessly any belief in a con-

scious life hereafter, what did this matter? There remained great

comfort in the thought that every one could live on in his

children and children's children through the virtue of that pot-

ency which lies in the mass of one's own immortal-cells. So it

was thought to be each one's duty to work for the good of one's

children, for the sake of these immortal-cells. What did self-

sacrifice matter if it were for the good of the immortal species

in which a particle of one's own soul lived on eternally! This

seemed truth, indeed, which was equal to anything that was

capable of saving the folks of the earth from that path of des-

truction they were heading for. Alien religious thought had

worked enough evil already. It had succeeded in uprooting

men out of the soil of their own racial inheritance, making them

careless in their ancestral love and reverence, as well as careless

in their duties to posterity. But this new wisdom was neither

of any avail as it was so improperly constructed on the duties

to race. It remained powerless because it could neither gratify

man's desire for eternal-life nor could it make men holy. At

the best it was merely capable of inspiring a desire to do social

work. The true secret of evolution it had not perceived!

Inspite of all this the Evolution-History remains the well

from which, when philosophical-Cognisance (Erkenntnis) and

soul-living (Erleben der Seele) are coupled to its truths, the true

1 60

meaning can be drawn concerning human-life, the obligation

of death, the inborn human-imperfection, as well as the ful-

filment of the immortal-will.

Let us now turn to our oldest ancestor, the "protozoon".

It is a very insignificant little forefather, infinitesmally small,

and looks like a sack of jelly. If we observe it closely we shall

note that it exhibits the same marks of life as the higher orga-

nised species show: It searches food, digests it chemically,

evacuates the waste and grows exactly like all the higher kinds

of living beings do. Although it does not yet possess proper

organs for this purpose, yet it can stretch its protoplasma body

into artificial legs called "Pseudopodian" with which it can

clutch its food and more about with. What impresses us most

is that it can feel (irritability), that means to say it gives response

to its surroundings in its own particular way. Notwithstanding

these powers, however, its construction is very primitive when

compared to the multicell. The most important pan is its nucleus

which is inside its tiny protoplasma-body. The nucleus is the

bearer of that potency which once enabled that grand, almost

inconceivable, flight of development. As soon as such a prim-

itive being has attained to certain stage of growth, very com-

plicated and likewise interesting happenings take place within

the nucleus, after which it divides into two. Then gradually

the plasma-body also divides into two, tightening itself up so,

that two independent daughter-animals arise from out of the

parent-body, each to live its life separately from now onwards.

Let us emphasize the word 'live'; for here is revealed the

greatest wonder which has happened since the existence of the

world. The more we ponder over the fact that all of us are

consecrated to death and therefore so used to death, the greater

this miracle appears.

It happens like this. The unicell divides and subdivides but

not to age and die after a certain number of times. On the

161

contrary, the melting of the parent-body into daughter animals

is one continuously unchecked process. Of-course, nearly all these

primitive cells suffer death accidently, at some time or another!

The first dies of thirst, the second of hunger, the third dies of

frost and the fourth is eaten up etc. But not all suffer accidents.

Under favourable conditions all could live on forever. Old age

and death in the 'natural' way is not their lot; so that we might

say the little plasma-cell we are looking at under the microscope

is indeed an immortal little fellow, so ancient as to count millions

of years. Theoretically speaking, we might assume, like many

scientists declare, that once upon a time it was carried with

the cosmic dust on to our earth, and at the end of the world

will land in like manner on to another planet with the purpose

of evolving into higher beings or to divide and subdivide etern-

ally. Therefore the unicell possesses the power to live forever.

The scientific discoverer of this fact called it "Potential Immor-

tality". Practically speaking, of-course, all these potentially

immortal little beings succumb some time or other to "Accident-

al Death". On the last day most certainly.

For the moment it seems almost unimaginable that on this

earth there is life which is not under the sway of irrevocable

old age and natural-death. When this scientific discovery was

made the times were very given to materialism, so that it goes

without saying that it was attacked in the usual ugly way. This

was twofold. At first it was ridiculed and then forgotten.

Evidently when a fact is unpleasant, the only help is to ignore

and shun it. And so it happened that one of the greatest truths

which men have ever been priviledged to gain was suffered to

be treated so ignobly.

Prof. Weismann, the famous zoologist, who, for his time,

possessed a rare understanding for philosophy although he

neglected to let it fructify his research, termed this new wonder

the "Potential Immortality" of the unicell. This was an excellent

162

pronouncement in that it implied that the unicell was immune

to natural death; that the usual way of aging and dying did not

form the contents of the last act of its life. In the lectures 4 he

delivered expounding this fact, Professor Weismann used words

which, although brief, show how deeply he was concerned in-

wardly with the importance of this cognisance. The words he

used were: "With my thesis concerning the 'potential immortal-

ity* I intend nothing more or less than to bring science to realise

the fact that between the unicellular and multicellular-organisms

there lies the introduction of natural, that is normal death".

Needless to say, from his contempararies he merely harvested

ridicule. No less an one than Buetschli confronted him with the

fact that a perpetuum mobile could not exist. This shows clearly

how far natural science had sunk into the arms of materialism

if one of its most capable and conscientious researchers could

compare a living cell to a machine!

After the ridicule and contradiction had subsided, there follow-

ed a time of relief when hopes went high that this vexing and

incomprehensible question (potential immortality) should be

settled and done away with once and for all. It had been ob-

served that certain kinds of "Ciliates" (a higher species of one-

celled being) exhibited periodically, after several generations of

dividing and subdividing, a certain tendency to lay themselves

one upon the other, either to copulate, that is, in the union of

nucleus and cell-body, to melt permanently one into another,

or to separate again, after having exchanged halves of the

nucleus germ-substance with each other, This (amphimixis) was

considered to be the method which the unicell undertook in

order to rejuvenate and escape natural death. (S. Maupas "Re-

jeunissement Karyiogamique"). Now, if, really rejuvenation

was the main object in view, which incidently is not proven,

* "Discourses on the Theory of Heredity" by August Wcismann. Publishers: Messrs.

Gustav Fischer, Jena.

163

and all the unicelled beings practiced amphimixis, which they

certainly do not, this fact, nevertheless would not suffice to

refute the existence of the potential immortality. It is essential

that the unicell also fulfils certain conditions of life, and the

amphimixis, no doubt, is a practice belonging to certain kinds

of unicellular beings. But this fact there is no gainsaying. Every

living thing which is once subject to the coercive laws of

natural-death cannot escape it subsequently. To these laws the

unicell makes expception, and herein lies it potential immor-

tality. Luckily, Weismann, himself, was able to bring forth

excellent material in aid of his own theory. Fate priviledged

him to silence the opposition of his contemporaries. It was

indeed fortunate for his theory that Weismann experienced

personally the controversies that went on, for, with the weapons

of his own knowledge, he overcame all the hostile attacks. But

since I have revealed to the public what a great philosophical

truth his scientific discovery signifies to be, and how easy it

makes it for us to understand the evolution of life, and why

death had to be, all the errors, long ago refuted, are being brought

to life again in order to throw dust in the eyes of the secular-

world; in men's terrible anxiety for the life of Christianity!

But behold! For a second time this marvellous truth could

not be refuted. Therefore it was ignored. Let us not be any

partner in this error, but rather let us look at it in the full light

of our consciousness.

Ever since man has been able to comprehend his surroundings

by means of his intellectual powers, he was aware of the cer-

tainty of death, and his firm belief was, that all living things

were subject to death. Indeed, all his conceptions, all his phi-

losophies, all his creations-of-art are pervaded with the idea

that all vitality on earth must of a merciless necessity end in

death; that death, in fact, is linked closely to all life. Even from

out of the darkest historical times, the truth of this comes

164

sounding upon our ears as if it were inexorable wisdom. There

is Hotar Aevata who sings in the Vedas that all life "is in the

chains of death, and is its complete slave", and now a truth

appears which reveals this to be illusion. A once unshakable

conception, which even the Maya despising Hindu learned to

respect. It only appeared to be true, but the reason why it could

dominate the minds of men so long was because the intelligence

of man had not yet discovered the microscope, which was ne-

cessary to perceive and observe the life of the potentially

immortal little beings. What an irony of fate it appears to be,

that, after thousands of years, when at last the illusion can be

unveiled, the eye of the researcher has grown so dim; the im-

portance of the new truth goes unperceived, while one could

have expected it to shake all the realms of men's conceptions

indicating as it did that the life-immortal for each individual

was indeed a reality.

There is something overwhelming in the thought, that, through-

out thousands and thousands of years, our earth was unaquainted

with the fetters of irrevocable death, that, notwithstanding the

fact that accidental death was always happening, death as a

must-be never occurred. And we might be forgiven, if, at first

thought, we claim the higher ascent of death-bef alien-beings to

be no progress. Is not the agony of death terrible? The believers

as well as the decriers of a beyond are both alike in despair,

when confronted with the unimaginable fact that a personality

through the might of death should be extinguished. When any

one we love suddenly dies, who has been all to us in life, and

whose ways and manners are still so fresh in our minds, it seems

at first quite impossible to believe that death means the cessation

of all this, that once was ours. Even those, who believe in a life-

here-after, are shattered, when it is born on them that all of

that which went to make up the personality of him who has

just died cannot accompany him into the beyond, but must be

165

left behind. It is the "must" attached to the fact which makes

it so incomprehensible. When we imagine, that long ages ago

the earth was spared this bitter "Must be", we are tempted to

think it might have been a better world; to a healthy person more

enchanting surely, without this bitter compulsion. Has not that

strong desire for self-preservation, innate in all of us, which

once was the form-creating-will of all the things visible to us,

been rendered cruelly and ridiculously hostile in having been

confronted with the fact of death's inevitability? What made

it so impossible to preserve that state of potential-immortality

in the life of the multicelled plant and animal-species? Here we

might be tempted to answer, that the introduction of compuls-

ory death through old age and decline, or in short, as science

has it, normal death, was because the useless multiplying of

vitality should be put a stop to. This is an error. For in as much

as the accidents which happen continually in the general-struggle-

for-life can be the cause of preventing a too rapid increase of

life, potential immortality would not have stood in the way of

this regulation by virtue of the accidental death over which it

has no control. As it is, a limit already exists which nature her-

self has set to control the growth of vitality. Of all those num-

bers of death-fated multi-cells, only two, on the average, of

every original pair are allowed to multiply. Only man was

allowed to diverge from this rule. His powers of reasoning

released him from the general rule existing in nature (the un-

changeability of the numbers). If he wanted to he could repro-

duce his kind in any number he liked, while for all the other

multicelled-beings, the number of their kind remained unchange-

able. Therefore we note, that all those in the fetters of natural

death, also die accidently in numbers incalculable, before ever

they reach the stage when they can multiply. Under these

circumstances the state of potential-immortality could have

been maintained. Therefore it would have been of no real

1 66

moment, if, by the virtue of their potential state of immortality,

399 998 out of 400 000 ova of one pair of herrings perished

before arriving to the stage of reproduction, or the 400 000 of

another pair all perished, or only 4 of another pair survived;

but what a difference this all would have made in the life on

our earth. How different would all our hopes and longings be,

how different the religions and philosophies. What a different

kind of art would there be, and above all, how differently

should we think of death. Death would often happen, but in

this case, it would be robbed of its coercive force. There would

be not aging, no decline of bodily and spiritual-powers after a

certain age had been arrived at. Instead, there would be a con-

tinual rejoicing in eternal youth. In our very midst there would

exist ancient denizens of the earth; all those who had managed

to escape accidental death. They would possess wisdom which

had accumulated within the course of thousands of years, and

would be radiant still with the beauty of youth. Although the

probability of death would be always lurking somewhere and

at some time, there would still be no-one who could predict for

certain when it would occur. All would have the right to hope

for eternal life, without however being doomed to a fate like

the "Flying Dutchman" or "Ahasver" of the legend experienced.

There would be no compulsion to live either; for the daily

threatening accidental death could be made voluntary at any

time. But the realisation of a 1000, nay even a 100 years, would

be such a rare event, as to make it a good fortune which was

well worth looking forward to. Not until we can fully com-

prehend the bliss which such a kingly freedom over life and

death would bring, shall we be capacitated to grasp, in all the

fullness of its pain, the agonising alternative: So accustomed

are we to be fettered to old age and death. As fate, in this way,

so mercilessly trampled down the Will-to-selfpreservation, men

naturally were caused, since they had created for themselves

167

a consolation creed of immortality, to succumb to the appalling

assumption, that the immortal life after death made up for

obligatory death. That to live eternally could be just as fetter-

ing and tormenting, and the much-lauded heavenly bliss was

nothing else than the fate of Ahasver of the legend did not

enter the mind of men. Anyhow it consoled man. He became

reconciled to the thought of normal-death.

Now, there is still another question which is also liable to

torment us. Why could not that sublime bliss (the state of

potential-immortality) be maintained in the manycelled beings

since man, in being able to understand it, lent it its significance?

Now, was it altogether impossible, or was it really the fault of

the conditions which vitality was subject to on our earth? Let

us still ponder on for we are nearing the holy mystery.

All life which once has made its appearance (Erscheinung),

on the visible scene (Welt der Erscheinung), is possessed of the

ardent desire (the will) to remain visible. That an Immortal-

Will (Unsterblichkeitswille) pervades all life, even the crassest

materialist cannot deny, although he thinks it fitter to give it

another name, more becoming and less foreboding to his own

viewpoint (Weltanschauung). He calls it the "Preservation-

Instinct". From this will spring all deeds, or, when we speak

materialistically, it "responds to its environment". The single-

celled- being sees this will fulfilled through its potential immort-

ality. (Let us stop for a moment to recall the protozoan to our

minds). Besides the anxiety to escape accidental death, philo-

sophically speaking, there exists no other impetus at all to cause

this will to change its form and also accordingly its life-condit-

ions. Eventually, the single reason for it to do so would be,

when its potential immortality was threatened through acci-

dental death overwhelming.

Now, is this circumstance plausible enough to justify, philo-

sophically speaking, the great change which took place in the

1 68

potentially- immortal one-celled kingdom? In face of the trem-

endous reproduction of the unicelled species, it became a necess-

ity*. Death became more and more frequent, through a twofold

cause. First of all the struggle-for-life became gradually keener

and keener, and then the want for food. Prior to this, the self-

preservation-will, unalarmed, could well be satisfied with the

visible form it possessed; But when danger began to lurk every-

where, a gradually increasing instinct compelled it to improve

its weapons-of-defence. They were projected into visibility

(Erscheinung).This means to say, in other words: the self -preserv-

ation-will was compelled to achieve the form of a higher or-

ganised species. The "Varieties" were the means. In this deve-

lopment, natural selection (Darwin's doctrine) aided, in that

the single individual which had really achieved the more dist-

inctly higher form maintained, as a consequence, its life. That

the minutest differenciation, however, was continually acce-

lerated through selection and bequeathment is hardly conceiv-

able, and we must reject this idea from our philosophical

thought, and leave it to the Darwinians. The first beginning

making for the higher organisation, which, by the way, the

unicell, in general, could make little use of in its tremendous

struggle, was put forth by the self-preservation-will in numbers

and numbers of individuals, so that naturally in the ones that

survived the general struggle and multiplied, it was also to be

found, but a certain stage of a noticeably more pronounced

achievement in the weapons of defence had to be attained before

it can be said that selection, for its part, could aid mechanically

the best-equipped in the process of reproduction. The more we

emphasize the fact that it was the self-preservation-will which

was the main factor in the creation of form in the higher species,

and not natural-selection, which played only a secondary, or

* The observations which have been made of bacteria show how trencndous the

continual natural increase of the unicellular organisms are, so that famine and destruction

through the increase of other kinds of unccellular organisms is almost inevitable.

169

"passive" part, the more will our argument seem to stand in

contradiction to the prevailing scientific conception concerning

the bequeathment of aquired characteristics. Not until the

whole edifice of our view-point has been completely erected

will it be possible to obtain a proper view of the facts concern-

ing the bequeathment of aquired characteristics, which to the

materialists seems such an impenetrable and contradictory field

of science. In passing, however, we may state that this part-

icular question of heredity does not stand in the way of the

argument we have just being giving.

Through the force of innumerable facts, the most important

of which we shall refer to later, it stands as proven, that the

self-preservation-will was the cause of the "variety" from which

the higher organism originated and the development which

afterwards steadily took place. It was not selection; for this

was of minor importance from the simple fact that the applied

organs were useless in the struggle-of-life going on at that time.

Hence, it was a form-creating-will which strove, albeit uncon-

sciously, towards an aim; the completion of an organ. Let us try

to understand this properly first, in order to be able to under-

stand afterwards how all the different species were brought

about.

The first transformation which the self-preservation-will

undertook was the better equipment of the unicell in the great

time of danger. We term this achievement the higher species. The

unicell was able to achieve within its own cell-body, in the most

primitive fashion, so much, what later, the multicell could only

achieve through the application of complete organs and the di-

vision of labour. It is remarkable to note how the division of

labour sets in within the body of the simple little cell. The

nucleus maintains the most important and vital function. While

it is dividing into two it differenciates into the great-nucleus and

the small-nucleus. The first takes on the function associated with

170

nourishment and the second for reproduction. In the process of

dividing and subdividing, only the micronucleus maintains and

bequeathes the heredity-substance, which goes into equal parts

into the daughter cells and by the amphimixis melts into the

other cells. Furthermore, we can perceive something like a blister

which rhythmically expands and contracts as if 'breathing were

its function, a structure which we can compare to our lungs.

Within the interior of the cell itself there is another suchlike

structure, a contractile vacuole, which acts like a simple kidney,

exactly like the kidney acts in the higher species. The cell-jelly

or protoplasm divides into a hard enclosing wall and an interior;

delicate protoplasmic-hairs or ciliar, whose rhythmical beating

drives the organism from place to place, protrude from the out-

ward wall. They are also organs of perceptibility. Many of the

unicells have also a mouth or gullet and farther an excretory

organ. Thus equipped, the unicell, of-course, is better facilitated

to move about quicker, and being robuster through the ectoplasm

it is far better protected against its enemies. Digestion does not

appear to occupy all the cell-parts; a circumstance which also

renders escape much easier.

But there is something particular going on which makes us

attentive. The great-kernel, or macronucleus, which was solely

concerned with the work of digestion, perishes after its work of

division is done, whereas, the small kernel, or micronucleus

remains. After dividing into two equal daughter-cells, a new

great kernel liberates afresh. Observe now, how the uncanny

spectre, called natural death has crept, almost unnoticed and

without much ado, into the kingdom of the living immortals.

Here the insatiable one behaves gently and humbly, demanding

but a small sacrifice from the precious immortal good of life; the

macronucleus.

The amphimixis impulse, which also makes itself felt in the

higher types of these simple cells, is responsible for the rapid

'7*

increase of the multitudinous variety of unicell forms. In the

intimate mixture of the heredity substance, the rise was given to

all the manifold possibilities. It was in this process that the

slightest varieties were intimately mixed and transmitted to

succeeding generations. As each of these new kind of organisms

met with hostility on the part of all the others, the danger grew

in the same degree as the more manifold and better equipped

they had become. Therefore it is not difficult to imagine, that,

notwithstanding all the benefits which had been gained for the

struggle-for-life in general, through the so-called division of

labour taken on by the single cells-parts, the Immortal-Will

(Unsterblichkeitswille), nevertheless, fell a prey to danger,

through the overwhelming power of accidental death. In order

to escape this, (life is essential for the realisation of immortality)

the self-preservation-will or the Immortal-Will suffered once

again the might of a still greater impetus which drove it to seek

new ways by the help of the transformation of its visible appear-

ance. (Erscheimmg).

If we equip ourselves with the necessary means and patience

to observe the life of these single-cells, we shall get the chance

of seeing how many of these little animals, sometimes over 50

in number, lay their cell-bodies one upon the other. They

remain in this close connection quite a long period of their lives,

without however, as in the case of the amphimixis, exchanging

any part of the nucleus, or melting one into the other before

parting again. Roux (scientist) interpreted this habit, calling it

mutual-attraction. As this peculiar habit is not always and not

everywhere happening, (for if it were, we should hardly meet

a single cell alone) but happens only occasionally between cert-

ain beings of the same kind, we presume that it is the mani-

festation of the first beginnings of the feeling we call affection

or pleasure at being in one another's company. I forgot to say

that science gave it the name of "cytotropism". May be, too, in

17*

times of danger, the self -preservation-will enhanced this in-

stinct in certain unicells. Be it as it may, the daughter cells do

not divide as they did at first to lead an independent life, but

the division-products remain) attached, and through further

division and tightening-up and remaining attached, they form

a little colony of cells which hang together. Among the algae

which colour the river reeds brown and the ponds green, forms

of these simplest cell-colonies can be found which consist of 16

cells. One of these oldest multicells is called the "Pandorina".

In one sense it is a kind of between-form. Still it greatly resembl-

es the unicells, so that the individual cell could be taken to be

protozoa which were held together through the power of cyto-

tropism. Each cell resembles exatly the other, consisting each of

cytroplasm, nucleus, contractile vacuoles, flagella, eyespot and

chlorophyllmass, and each cell fulfils its life-duty in the manner

of the unicell. It partakes of food, moves about by means of

flagella and reproduces its kind through division as every uni-

cell does into two separate daughter-cells. These spontaneously

divide and subdivide, but hang still together, and when 16 cells

have been gained, the new multicell has appeared and flows forth

as an independant pandorina. Because these higher types behave

like all the unicells do, we might be tempted to think the cell-

colonies are still potentially immortal. But at the next step a

change has taken place. Notwithstanding its apparent insigni-

ficance and immateriality in the struggle-for-life, this little

change decides the fate of all plant and animal-life! "Natural

death", which means death from old age and is inevitable, once

so powerless over the unicells, makes its appearance now per-

emptorily and demands its sacrifice. Exactly as it was sung in

the Vedas, "death completely befell" all those multicellular-

beings which belonged to a higher developed stage than the

pandorina.

A species of the algae-family which is closely related to the

pandorina is called "Volvox". It is the first kind of multicells

which consist of two different kinds of cells. The first is smaller

and grouped closely together in larger numbers and form the

body wall. They are all equipped with flagella, which, in whipp-

ing rhythmically, enable the tiny animal globe to move about

the water. They minister to its wants in feeding and removing

waste matter. In short, their function is the division of labour

in the struggle-for-life, and do not serve at all as reproductive

elements.

This novel circumstance which appears here for the first time

in the process of development is of tremendous importance.

While these cells have by no means given up the potency to

reproduce by division, yet their divided cells begin to develop

into cells which strictly desire to be akin, that means to say, they

bequeath the functions which have solely to do with the maint-

enance of existence and nothing at all with reproduction.

On the inner wall of this hollow cell-sphere a few large cells

protrude into the watery fluid of the hollow interior. These cells

are the second kind. For their part, they have lost the

potency of forming any flagella wherewith to move about.

Neither are they capable of gathering food, but instead allow

the other cells to minister to their wants and protect them from

enemy attacks. Well-cared for, (being altogether the greatest

treasure of the cell-state) they lie doing "sweet nothing", until

one day, each one divides and reproduces, developing then into

a completely new globular cell-colony, called volvox. Then,

with the rupture of the parent-wall, they escape together with

all the like constructed youth, to start the same life all over

again.

What happens to the collapsed globular cell which has been

left behind? In losing its form, it sinks to earth and dies, but not

through any mishap, or want of food or attack of enemies, but

simply because it cannot live on any longer. Inevitable, natural

death, as the final change in life, has swayed its scepter for the

very first time!

From now onwards, its prey is never once allowed to escape

out of its hands. All the animals and plants descending from

that globe-like algae called volvox are submitted to him, for

they are all comprised of different cells. All of these undergo

such marvellous changes within the course of development, that

in the end hardly any resemblance of the prime cell is left. The

germ-cells make the exception. They remain always the same

except for a few slight changes undertaken for the sake of prac-

ticability. The former cells range themselves in groups of

similar tissue for the purpose of building up organs. These organs

then function for the state, for they have lost altogether the

potency to be able to construct germ-cells. Therefore they are

incapacitated forever to reproduce beings of their own kind.

In fact, as is the case of many higher kinds of animal species,

many indeed have throughly lost the capacity of building up a

newer kind of tissue *, and instead there is produced a lower

kind of tissue. Like volvox these cells also are subject to old age

and death, although, unlike volvox, the higher types of cell-

colonies do not necessarily die after having once fulfilled the

office of reproduction.

Before dedicating ourselves to a nearer study of the effects

which were caused by "Celldifferenciation", let us try first to

conceive a completely clear conception of the "Somacells".

These cells work in cooperation, and form the "body" of the

multicellular individual. Thus then, according to the historical

sense of the evolution history, as well as according to the ex-

planations which will follow here, the cell-state of the animal

is made up in this way. All the cells give the animal its appear-

ance and are called "Soma" or body-cells except for a few

* For instance, in this way there arise connective tissue cells in place of higher

organised liver-cells.

175

cells which are in the service of reproduction only. In order to

gain a clear and distinct idea of what is meant by "body", it

is essential to be able to discriminate from the usual way of

thinking. In general, body and germ-cell are thrown together

quite promiscuously. When the word 'body' (Erscheinung) is used,

it is generally understood to mean that visible something as

standing in opposition to the invisible inner life (unsichtbaren

inneren Leben) which exists in all the cells, the "Soul" as it is

called, or the "Thing Itself" as Kant has termed it.

Granted that these customary terms were but used in the

endeavour to discriminate the mortal part from the immortal,

it still remains to be stated that in the history of evolution

endeavours to do the same are also apparent. The insurmount-

able gap which the appearance of natural death has caused lies

yawning between the body-cell and the germ-cells. The body-

cells, because of their mortal character, are death-befallen, while

the germ-cells are 'potentially* immortal. The immortal life

is realised, in that, a part of the germ-cells, through the act of

reproduction, is handed down to posterity. In the case of the

unicells there exists the actual potency to realise immortality.

What has been gained through this huge sacrifice?

Where the algae, or volvox is concerned, nothing at all has

been gained. In the general struggle-for-life, which they are

constantly exposed to, they are neither better protected, nor

can they multiply in greater numbers than the pandorina. But

the process of development and exfoliation of newer species

yields another aspect, and seen from this aspect, it is obvious

that very much indeed has been gained.

In having given up the capacity of reproduction, the body-

cells diminished in importance. As soon as the daughter-colonies

could be liberated, their fate turned into tragedy. They were

compelled to age and die, for 'merely living', for sheer exist-

176

ence sake, was not their lot. Yet, vitality, when thought of as

a whole, had gained tremendous possibilities of development.

What a startling potency must that have been which gave those

cells, sacrificed to death, a power so mighty, as to make them

transform themselves and rise to the level of a higher developed

stage. To the eternal germ-cells, self-satisfied in the fullness

of their wishes, such a power was never granted and never will

be granted. Let us stay a moment to think of the ascent made

from volvox to man, and compare this lengthy way to the course

of development, so uneventful of any change, which was made

from the first unicell towards volvox. It will be seen then, that

the sacrifice, which the body or "somata" made at that time to

death, was not too great. What did it matter if only a few

plants and animals escaped accidental death after such a short

time of youth? At the sight now of animal, plant and human-

life our hearts expand with reverence, for they are the product

of a power-of-transformation most beautiful and a development

most grand. Nor can we forget how the cells 'differentiated',

gaining weapons of a more excellent type, at becoming in the

end a higher kind of species! Also, that, inspite of all the improve-

ments which followed in the equipment, the danger of death

still existed in the world. The greater the perfection of the

multicells grew, the more dangerous the enemy grew, for all

"Life's Strugglers" were equally well equipped, danger kept

apace with every new improvement. Therefore how justified

it is to say that the various multicells, in order to achieve the

level of a higher organisation, drove each other to perfection

in their mutual endeavours!

Moreover the fact, that 'accidental death* still exists in the

world inspite of everything accomplished to escape it, is not

so saddening in face of all the loveliness effected by the cell-

differentiation. It is pleasing to know that both animal and plant

are absolutely unconscious of the fate that awaits them, that,

while struggling, suffering and enjoying, they live their lives

as if neither the accidental nor natural death awaited them!

One truth has left an indelible imprint on our souls: As we

lingered at the side of the oldest denizen of the earth, we be-

came aware of the fact, that natural death, that is; age, decline

and death is not the last inevitable change which all life must

experience. The soma-cells only are 'completely death befallen*.

This knowledge makes us turn with reverence to the old relig-

ious myths once again, for inspite of all their fallacies this

very same truth they also contained. Reason has confirmed to us

a twofold fact, that all the primitive living beings belonging to

our earth possess a state of immortality, which, in a later generat-

ion, was lost forever. The voice of wisdom has always preached

this; the folks of the earth were always inclined to listen! Has

not a paradise lost and a lost bliss 'where death was not* been

sung in every form and shape in legend and religious-myth, as

if a memory or "Mneme" of our oldest ancestors, slumbering

in the subconscious-soul of man, had been awakened in the

poets of the myths?

Comments

Post a Comment