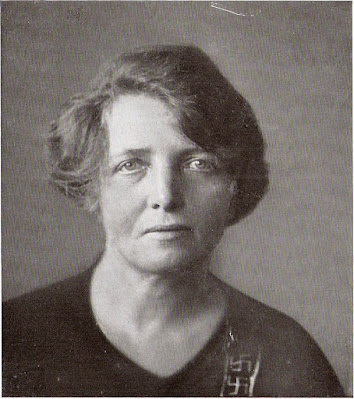

Conclusion to Triump of the Immortal Will, + Notes (pt.4 Triumph of the Immortal Will by Mathilde Ludendorff)

Donate: https://www.patreon.com/VincentBruno

I've read much of the concluding chapters of Mathilde Ludendorff's Triumph of the Immotal Will and to be honest, I can't understand it so I can't make any further commentary, though I do know she supports the idea of free will, which I do not support. I do not know how she gets to polytheism or if she really does. This is very deep metaphysical jargon, if you are a Nordic person and can understand this and find comfort in it, I suggest you take this religion if you are in need of one... or if you are trying to use spirituality to unite Nordic people. I will continue to try to find commentaries on her work which are broken down in ways that are easy to understand. If anyone can understand this and knows how to explain it to me you may contact me at Vincent.Bruno.1229@gmail.com.

Natural Death and Reason

The materialistic century persevered in its attitude of in-

difference towards the "Potential-Immortality" characterising

the unicellular beings, but, with an infatuation without its

parallel in history it fixed its attention on to the cognate

immortality of the germ-cells. This verged almost on extasy,

although even more devotion was attached to the decay of the

soma-cells. It was not so much the doctrine of the "Mortality

of the soul", but the subordination of the brain to the perpetual

germ-cells (the bearers of the species) which proved to be such

a source of satisfaction to the materialists. Therefore it is not

amazing to find the sober, matter of fact "Struggler-for-Live"

so self-satisfied, for indeed, when seen in the light of that import-

ance that was attached to the germ-cells, how insignificant was

everything else which once had been valued as "Soul". Even the

"Purpose" of the brain, the bearer of consciousness, was for the

reproduction of the kind, for itself, one day did vanish; all the

marvellous achievements of the brain-cells, those chemical and

physical processes (Kispert's "Enkynemata") merely happened

in order to serve the perpetual species. One step in the process

of development was thought to be particularly salutary; After

the act of reproduction, the body of the higher animals could

still live on for a while. In the case of man, a species of the higher

"Mammalia", this fact grew into great significance: Because of

the better construction of his brain-cells man was capacitated

to undertake highly intellectual work, the "purpose" of which

it was thought was for the sake of facilitating the struggle-for-

life, not only for his own off-spring, but for his species in

general. This mortified the soul completely. What a fall it was

from those giddy heights to which Kant's philosophy had

brought it such a short time ago. Had it not been upheld that,

among all the living beings, man alone was capable of distinguish-

ing his surroundings? That, by virtue of his reason, the cosmos

was created out of the diaos of the world-of-appearances (Er-

scheinungswelt) and was consciously perceived for the first time;

because reason was able to arrange for him the objects of his

senses in order, as man was the conscious state of the visible

world (Erscheinungswelt)? Thus then the soul of man had fallen

from the height of heights; the height of the soul which gave

him the priviledge of holding a completely unique position in

the world. Since the soul's fall man had grown to the small

stature of being something different to the rest of the species in

that he was the last in the line of a 'differentiating' development.

He stood at the top of the Mammalia. The highest standard of

importance to which his transitory soma was capable of was

becoming the bearer of the immortal cells of reproduction.

When a world-view-point (Weltanschauung) such as this one,

is allowed to determine religious thought, it is not startling to

find that epoch lost in an abyss of soberness. The suppressed

soul is capable of rising to a certain 'social' usefulness, but in

every other way it degenerates miserably, although in a differ-

ent manner to what it does when influenced by religions that

are against reason and science. The results of this way in which

the soul is being mortified are: brutality in the general struggle-

for-existence, fraud, sly cunning, greed of money and the crav-

ing to gain advantage of others.

Let us tread different ways to all these on our journey of

observation. We shall be repayed with a wonderful cognisance

(Erkenntnis) concerning natural-death which again will lead us

to a new Godcognisance (Gotterkenntnis) according to which

1 80

we can live our lives in that fullness which past religions sus-

pected to exist although they never could achieve it. By the

means of our Cognisance (Erkenntnis) the soul will be able to

rise again. The heights it can achieve are so exalted, that the

glorious height to which once it was raised through Kant's

philosophy will seem low; verily the august throne for the

human soul when it fulfils itself according to its divine rights.

It was not a mechanically working process of selection, but

a dawning will (as we shall soon be near proving) which deter-

mined the step towards the mortality of the somata (body-cells).

For as soon as we stop to observe the pandorina, we are able to

notice that all its cells still possess the same attributes which

belong to the germ-cells; hence, potential immortality also. Its

near relative, volvox, however, is already condemned to death.

We feel certain that, in comparison, the pandorina-state was

not less favourable than the one where, for the sake of practic-

ability in the struggle-for-life, that grand mysterious change

which has proved so full of tragedy to posterity, was necessary.

On the contrary! As the sixteen cells of the pandorina were still

capable at any time to form daughter-colonies, whereas the

volvox only once in a life time, it is obvious from this fact that

the pandorina was just as productive as its relation, so that it

strains the imagination to look at the matter from the Dar-

winian standpoint, for, if selection really counts, the pandorina

ought to have surplanted the volvox form. Conceptions, formed

in the mere light of the mechanical, fail just as completely to

throw light into the matter here as it does everywhere else in

the history-of-evolution when the fundamental idea is touched

on. (The ascent from the deepest unconsciousness to the highest

consciousness). Here the fact comes to light that only an inner

Will could have liberated that energy which caused the trans-

formations. Matters are similar in the case of the nervesystem.

The nerve-system was the carrier of all those magnificent po-

181

tencies which exfoliated later into conscious soul-life. Here also

it is futile to want to explain this in the light of the mere

mechanical, for one reason, and that is that the beginnings to

the realisation of this were of no use at all to the individual in

the struggle-for-existence at that time. But clearly apparent, on

the other hand, is the immortal-will striving in its magnificent

work of development to gain the state of consciousness, not-

withstanding the fact that the single individual itself was com-

pletely unconscious of its presence. On its way to progress, the

immortal-will had to encounter a twofold circumstance of cog-

nate importance. First, there was always the danger of the

moment, and secondly the illustrious aim in view; the conscious

state of life. It seems a wonderful thing for our cognisance that

all the transformations, undertaken for the sake of this great

aim in view, were, in their first beginnings, of so little import-

ance in the struggle-for-life, that we surely can be pardoned

if we claim the conspicuousness of this fact to be especially

intended to facilitate the work of man on his way to truth.

Only from a certain stage onward did these constructions be-

come of any importance in the struggle-for-life and not until

then only could they have received any support from selection,

in the Darwinian sense. We must wait still a little while longer

before the mystery can be unfathomed; why this sublime Will

to consciousness, while remaining absent in the 'germ-cell in

perpetual existence', took sudden possession of the soma-cells

as soon as these had fallen a victim to natural-death.

In opposition to this transformation, the aim of which was

to gain a higher state of consciousness, but whose faint be-

ginnings were practically of little use to the single individual

in which it was striving to manifest itself, there was a whole

range of perfected constructions in the further process of deve-

lopment which to the species in question were certainly of use.

We are thinking here of all those characteristics which seem to

182

confirm Darwin's hypothesis, the study and explanation of

which are also mainly due to his earnest study and research

(mimicry). The remarkable thing, however, about the character-

istics which Darwin specialised in is this. When compared to

the most vital constructions their importance seems incidental,

and they have no direct connection at all with the grand evo-

lution aim, which was to achieve an ascent from the darkest

state of unconsciousness to the clearest state of a conscious soul-

life.

Now, if, in our desire to remain just, we do succeed in

imagining a mechanical origin of the above mentioned charac-

teristics, even then, it appears obvious to us, that a Will was

more probable than selection in the creation of the first organs,

although of-coursc selection lent its support later on. Therefore,

in face of these incontestible facts, we cannot avoid this con-

clusion! In the ascent from the unicellular-being up to man

the part which "Selection" played in the transformation-role

was the passive one, while the Immortal-Will (or Self -Preser-

vation- Will) was the active one.

Hence, in the scientific sense, we can say: the reason, why

all the cells struck out on their way to transformation and why

the soma-cells in particular were deprived of the power to repro-

duce, and therefore, as a consequence, their immortality, was

for the sole purpose of being helpful to the a : m of evolution.

How capable did the bereaved soma-cells now prove them-

selves to be in the creation of form! The extraordinary course

which the mortal individual was now called upon to undergo

is even beyond the imagination of the most fantastically-minded.

The more the lower species increased, the greater did the dang-

er to all grow. As a consequence, certain kinds of volvox were

obliged to fasten themselves to fixed places, and by the move-

ment of their tentacles convey the food towards themselves.

There was one very great advantage gained by this. A spot

183

could be chosen permanently which was certainly better than

the alternative of wandering about amidst dangers accompanied

by unfavourable conditions in respect to food, light and climate.

Posterity, however, gradually lost the power of ever again being

able to change their places. But their tentacles became the fitter.

In this way the plant, sometimes called the "Fettered Animal",

originated. Much indeed had been gained through the sacrifice

of freedom. Being always in the same spot the dangers en-

countered were likewise always the same. The cells, through con-

tinual differentiation, gained such practice, as to be able in the

end to adapt themselves wonderfully to those conditions in their

environment which were important to their lives. Indeed, as

danger grew less, this adaption grew supreme; so much so, that

by virtue of this fact the construction of plants, conditions of

climate, food, light and water were revealed to researchers as

if they had been written down in a book.

Algae, on the other hand, did not fetter themselves for the

sake of safety. Inspite of all the dangers, they would not forfeit

their freedom, so that they were obliged to pursue another

course of development. The continual change and the manifold

dangers they encountered did not permit of an adaptation which

was to meet a few emergencies only. This imperfection was

aptly made up for in another excellent way. The ever varying

changes which the desire for movement brought with it, gave

rise to the neccessity of a greater cell-change as well as combi-

nation of organs into cell-groups. Yet even this proved insuffic-

ient; for the multicelled being was obliged, above everything

else, to become instantly aware of what it might encounter from

out of its surroundings. Thus, there originated organs of per-

ception and nerve-cells, which gave the animal the ability to

judge from its own impressions and forewith conduct its res-

ponse. Guidance was obtained. Now this line was of such tre-

mendous issue as to completely distinguish animal from plant-

184

life within the course of development. In emergency, the self-

preservation- will had demanded from each a different course.

Indeed, animal and plant-life appear to be so different in the

expression of life and its achievement, that it renders it almost

impossible for the secular-world to believe they were once of

cognate origin. Evidently, the absence of any development in

the nerve-system made it possible in the plant-kind to maintain

the original relationship between body and germ-cells, so that

it can be said, the whole life-work of the body-cells were taken

up in serving the germ-cells. What might seem however to be

rather unnatural in this relationship is the tremendous size which

many plants achieve through the mighty increase of their body-

cells (in comparison to which, the germ-cells have no size at all),

and also the long life which they have been priviledged to attain

through the sacrifice of their freedom. (They had prefered to

adapt themselves to certain life-conditions instead of roaming

from place to place.)

The soma-cells of the animals, on the other hand, appear to

free themselves from the sole duty of serving the germ-cells,

especially after the nerve apparatus has developed. They appear

to be leading a life for themselves as well. This is especially

conspicuous in the body-cells of man, who is the highest of all

the living species.

Although the nerve-system, in its first beginnings, was simply

the humble reporter of the perceptions received from the outer

world, it was vouchsafed to become the best weapon of defence

in the struggle-for-life, especially after it had attained the

higher degrees of development. Mimicry, poison gas, claws or

the swift motion given through the power of the muscles was

nothing compared to the nerve apparatus in the matter of

defence. Nevertheless, it was impossible to ban danger alto-

gether, for the development which started in all the different

animals alike was simultaneous. What happened though was;

185

the struggle-for-life itself became more and more keen, so that

the self-preservation-will was practically driven to seek new

improvements.

As the development of the primitive-cell in the life of the

individual belonging to the higher species was very gradual,

inner fertilisation became necessary, that means to say, the

young, after being generated in the mother-body, were also

provided with reserve nourishment (reptiles, birds etc.). Among

the still higher organised species, the young are retained in the

mother-body and are not allowed to enter into the hostile world

until they are fully developed. Here, the 'inner fertilisation'

which demands the bodily connection of the parent-animals has

become essential. Long before, it was evident that the higher

species could not multiply to the same extent as the lower

species could, and for this reason it became imperative, should

the species not die out, to set a certain time apart which should

be dedicated to the reproduction of the kind. For this purpose,

contrary to the painless lives of their forefathers, there awak-

ened in the halfconscious creatures, the torture of sexual-desire

which simply drove them to multiply. And although this meant

a mighty step forward in the course of evolution, the unhappy

semiconscious creatures had to pay dearly for the better means

of defence! As danger was often very great when the animals

went in search of food, the self preservation-will had to be

overcome in that life, was jeopardised in order to save life from

famine. Therefore it became imperative that in these semicon-

scious beings, the craving for food should be felt so strongly as to

make them risk their very lives in order to satisfy it. Thus, for

the first time again something was being experienced which

before, in the lower species, had not been felt; the feeling of

hunger. The higher nerve-system lay like a curse on all the

animals who were blessed with its possession, in that, if it caused

craving to be felt, it also caused the pain to be felt which illness

1 86

and the wounds received in battle caused. Yet, the more consc-

ious the soul grew, the greater the comfort grew for all the

suffering. For the first time, animals felt pleasure in the act of

reproduction. Although it might be said that this sudden feeling

of pleasure stands in no right measure to the torments of desire

which previously had been suffered, it still remains the oldest

and most mighty fountain of joy. This reveals to us how full

of pain the lives of the subconscious "higher" animals are.

Seldom do they experience pleasure. Yet there is one great

blessing which lays her kind hand soothingly over their fate:

memory is still blunt. As soon their cravings are satisfied, all

the torments which inaugurated them, sink into oblivion. There-

fore, inspite of all the pain and fighting which go to make up their

poor lives, moments are experienced which are completely free

of any pain or suffering at all. Schopenhauer declares this state

of oblivion to be the only state in which mankind could find

happiness; but that was on account of the bitterness which

sometimes overwhelmed him, and because of his persistence

in denying man's consciously living God. He could not or

would not perceive that the only state which means happiness

to mankind is the state in which he is consciously living God.

Incidently speaking, even the mating-joy raises the animal

above this zero-point.

As the nerve-system proved to be such excellent weapon

of defence in the struggle-for-life, selection, from a certain

stage onwards furthered its development. When it became evid-

ent that it helped greatly the Will which was forming and

shaping creation on its way to consciousness, its development

became simply marvellous. For instance, the sense apparatuses

became very sensitive indeed. (It was their function to report

the happenings from the outer world.) Central organs deve-

loped (spinal-cord and brain, as in the case of the vertibrates)

which were receptive, and which gave the body-cells the com-

187

mand how to respond to the outer world. In the Mammalia they

gained specific importance. Those innate powers which slumber

in all living things began to reveal themselves very distinctly.

To use Schopenhauer's philosophical term, the "Thing Itself"

began to 'objectify* Itself. Here and there manifestations of

the Will could be encountered which were not exactly connected

with the self-preservation instinct. In the lower species the

instinct for food, defence or reproduction only is manifested,

but in the higher species a Will begins to manifest itself already

which decidedly has a permanent sense-of-direction, which in

man we should call 'character features' although of-course here

their origin is always still to be found in the self-preservation-

instinct.

Besides that permanent sense-of-direction, and those conscious

feelings of pain and pleasure which we have already mentioned,

there are still other feelings which already at this stage are

perceptible for their independence of the self-preservation-will

of both the individual and the species. In these feelings the soul

expresses itself, although, of-course not half so clearly and

distinctly as in man, and it requires a long time to observe them

at all. When the higher species of mammalia become domestic-

ated they become very noticeable, I should like to say: awak-

ened. The reason for it is the closer association with the consc-

ious soul of man. A good example of what I am trying to

explain is the dog. How often it will happen that the dog's

feeling of attachment to its master will cause it to overcome

its own indomitable Will-to-life, in order to save its master, a

deed, by the way, which otherwise would only save the life of

its brood. In general, it is the human-being, and not one of its

kind that is capable of inspiring such a keenly awakened feeling

of sympathy within the dog. The attitude of a dog, mourning

at the grave of its dead master, discarding even its food, tells

us with an authority unimpeachable, that there was something

188

in the life of that dog which was certainly of more value to it

than its own life was.

Finally that stage arrives when memory awakens. At earlier

stages, already, that faculty existed which could form concept-

ions of the impressions conducted by the sense-apparatuses and

maintain them in the soul. But gradually it grows stronger.

Soon, the way its own actions affected its surroundings remains

in the animal's memory, and its subsequent behaviour is the

manifestation of what we should call the experience-of-life.

Soon the power of understanding awakens. Although quite un-

consciously, it begins to apply the laws of causality. It arranges

its life-experience into time and space, although it is quite

unconscious itself of these facts. Conceptions of what goes on

around it begin to collect in its brain. But they just come up

to suit the animal-brain. This collection is divided into three

groups. All the objects which have proved of use in the life of

the animal belong to the first group. All which has done it harm,

to the second; the third group is composed of the rest, which

is of so little importance to the animal, that it is incapable of

forming any conception of this at all. Thus it can be truly said

of the animal: Nothing exists at all besides the useful or harm-

ful. The third group to the animal is the "to unov" (non-ex-

isting) of the Greeks. Although the sense-organs receive the

impression of them the brain does not think them worth storing

so that, in reality, they are not perceived at all. Why indeed

form conceptions of anything of such petty importance! That

which is merely useful or harmful alone fills the small humble

world in which the animal lives. The useful as well as the harm-

ful are very attentively watched, one might be tempted to say,

studied. Images of them are then imprinted on the memory

which are at once clear and ineffaceable. These images or con-

ceptions are not true to life of-course, neither are they composed

of the characteristics essential which go to make up an object,

189

for they carry the stamp of the mere animal mind. They are

composed solely of those signs which are important to that

animal whose attention they are just attracting. For instance,

the mouse and the dog will both possess ideas of the "cat", but

most probably both the ideas are very different from one

another. Each animal collects its own special kinds of concept-

ions. The lion's collection is different to the mole's, so that, in

truth, each lives in its own world, which is 'quite different* to

the others. In the brain of each different kind of animal there

exists a different image of the world. It is of infinite importance

for us to try and understand this sufficiently, for as soon as

we succeed, we shall also understand that each of our fellowmen

lives in a world of his own making. The conceptions which the

human-being also forms differ both in their nature as well as in

their profundity. A man whose mind sways only to the rhythm of

the struggle- for-life, and who is always bent on making a good

bargain, has little in common with a man who is filled with

a great sense of the Divine. Something else we shall understand

better if we observe the animal-soul closely. We know that

man has sprung originally from the very same stages of deve-

lopment, but some men there are who seem to have remained

just where the animal is. Although in school, already, these had

been given the benefit to learn and form conceptions of the

cultural-life, irrespective of their useful or harmful qualities

in the concern of earning a living, yet still they let these con-

ceptions all go, (sometimes already) while they are still young,

and put in their stead the old way of grouping, characteristic

to the animal. We know these three kinds of groups already.

They are the useful, the harmful and the indifferent. It is

simply amazing how narrow-minded a man can grow. Inspite

of all his good bringing-up, he will shrivel back into the animal

stage, and, more the shame, even beneath this, It is even more

amazing to watch how keen he will grow to know what is of

190

use to him or what of harm and how oblivious and indifferent-

he is to everything else. The very best example for the fall of

man can be found in the Darwinian period. Thanks to the

doctrine which taught that man belonged to the class of animals

that suckle their young, industrious endeavours were made to

justify it. Observe then this. Man, by the virtue of his spiritual

capacities really belongs to a class which is higher than the

animal species. His conception- world, however, has the power

to drag him back again to the animal state of mind, although

unlike the animal, he must retain the power of his memory,

for never again can he forget the past, or be oblivious of the

future. He has descended to become merely a bastard-like being,

which is neither man nor animal, but which is decidedly in-

ferior to the animal. During our discourse the occasion will

be given to us to occupy ourselves very often with such a kind

of human individual, for it is very important in respect to

certain other things to know well what his petty world of

conceptions is like. Therefore let us set to, to observe the

image which the animal-mind forms of the world around it.

When compared to the bounteous soul-life which has been

given to man, the intellectual-life of the mammalias appears

very meagre indeed. Yet, this state of soul-awakening which

has been attained in the animal is indeed sublime, as the be-

ginning was from a state of the deepest unconsciousness. Al-

ready such a change has taken place, as to make it appear as

if a tremendous gulf separated the beings with the awakening-

soul and the others which exist still in the monotonous state of

complete unconsciousness, so much so, as to make it almost be-

lievable that the antagonism could be felt, which exists between

mortality and the serving attitude of the body-cells towards

the eternal germ-cells. However the animal-world is still un-

encumbered. It has no need at all to solve the mystery concern-

ing life, for it knows nothing of a future. Even the most in-

191

telligent of its kind can never know that death awaits it and

is inevitable.

If we start from this last stage of evolution and wander up

the path leading to man's origin the discord is obvious which

the soma-cells caused when they determined, for the sake of

life, to give up their immortality and differentiate instead.

This discord has existed ever since; and as men failed to perceive

the idea of its origin, in that it was a part of evolution itself,

the mystery which hovered around it was never successfully

solved. All the hopes and desires of men in the ponderings of

their philosophies were in vain; all the soft deceptions contained

in the myths and the religious beliefs were of no avail. Now, as

we have already seen, it roots right back into the ages. Long

before animal and plant-life separated to strike out on different

paths the dice had fallen; at that time, when the cells of the

algae once divided into two of a different kind and when later

a daughter colony escaped with the rupture of the parent wall

(death). Therefore, the yearning for immortal-life should not

surprise us, for it is older than the hills. It existed in the breast

of man long before he could even think. The melancholy reali-

sation of death has brooded over his soul since times imme-

morable. We know that the Self -Preservation- Will or the

Immortal-Will is the essence of all life. We also know that it

exists just as well in the body-cells as it does in the germ-cells,

or else these would lack the impetus necessary to serve willingly

in the struggle-for- existence. Therefore we also know all about

the yearning for immortality which is rampant in the soul of

man. But simply because the desire is there, indeed even the

'aprioristical' certainty, this is not sufficient reason for us to

take it for granted that immortal-life exists. In every case, we

are obliged first, for the sake of truth, to allow for the possi-

bility of this. The certainty which men feel that immortal-life

exists is merely a 'memory' (Mneme) of a once experienced

192

immortal-life, a memory which now lies deep down in the

subconsciousness of mankind.

Let us now continue the history of growth. In doing so, let

us not give way to our own petty hopes and desires, or else our

vision will be marred and the truth we shall not perceive. The

animal-mind is so adequate (for-instance in the higher-species)

to cope with the dangers which surrounds the animal, that it is

really a kingly sight to watch the bravery of the animal when

it is in danger. However, two kinds of danger seem beyond its

powers to cope with. Man is the first danger, as he is far superior

in everything, and the second are the powers of nature because

the animal is utterly incapable of comprehending them. If man

should make use of the latter, he can overwhelm the bravest

beasts-of-prey. See how the tiger is cowed when it is encount-

ered with fire. Its expression is full of fear. (Human beings

look the same when they are in a similar situation and are

afraid of the devil). We can understand now why the animals

are apt to be restless and full of fear when a thunderstorm is

threatening.

The powers of nature were the sole enemies which could not

be overcome in the ages before man existed, for the simple

reason that all knowledge about them was lacking; in order to

lead a successful combat against the cosmical powers, the very

first essential is knowledge of the laws-of nature. A little more

is required, however, than the mere unconscious application

of the laws of causality and the arrangement in time and space

as the animal-mind achieves it. A fully conscious application of

these is necessary.

In just the way in which the Self-Preservation-Will sought

consciousness in ascending stage by stage in order to escape

death, the final mighty step in evolution was also made neces-

sary through the fear of death. The animal-mind was found

wanting. The happenings of nature were too great for it. So,

in that terrific time of the first ice-period, when hecatombs of

animals were being sacrificed, the self-preservation-will in one

of the exceptional few of those subconscious ancestors of ours

awakened to the state of consciousness which alone was com-

petent to venture the combat against the cosmic-powers. The

soul had awakened a degree higher; understanding had become

reason. And although the evolving changes might have been little

noticeable at the time, the effects themselves were tremendous.

No other step in the progress of evolution, not even the differ-

entiation of the algae-species was of such infinite importance

as this step was, for it gave man, as a token of it, the bounteous

kingdom of his thoughts. The becoming conscious of the causal-

coherency which linked the visible-world together gave birth

also to the ability which enabled man, not only to perceive the

visible-scene, but also to keep it in his memory, as well as form

conceptions of it. These conceptions stood objectively in di-

stinct relationship to one another. The possibility was hereby

given to form a conception consciously. This, of-course, was

of tremendous importance, especially when the conception of

"Self" could be formed, for then the cognising powers could

strengthen. Soon the feelings of time and space added them-

selves and were applied consciously like the law-of-causality

had been applied. In memory, events accordingly were arranged

in time and space. Past and future became recognised until, at

last, men were capable of creating a cosmos out of the chaos

of their surroundings. Now, the being able to apply consciously

the laws-of-causality was a great prerogative, but with one

stroke it changed the position of man completely. He stood

suddenly opposed to nature. This contract, the intellectual

sciences call the natural and unnatural actions of man. Now

this at first seems absurd as reason, together with all its logical

conclusions, is itself part and parcel of nature. Well and good,

but reason is not infallible. It is somehow, always open to de-

ception; it is always as likely to judge according to false appear-

ances as not. Erroneous assumptions as to the real cause are

frequently made. Thus, men are induced to come to false con-

clusions and false sims in life just as much as they will come

to false conclusions about the laws-of -nature and the meaning

of their own lives. This explains the reason why the innate

spiritual faculties are just as liable to shrivel up as they are to

exfoliate.

Yet, notwithstanding all the damage which man has been made

to suffer through the half -knowledge his reason will sometimes

gain; the benefits he has gained decidedly outweigh all his

sufferings. For instance, look how reason has facilitated the

battle for life. No end of possibilities have been opened to him.

Thanks to his reason man became the master of all the rest of

life. He put everything to his own use, in order that his life

might be maintained. Is this all?

If we take the trend of Darwinian thought to be right this

is all the advantage which man gained over the animal. And a

bitter conclusion we should have to come to as well, which would

be, that the stalwarts of finance, the multimillionairs, who, also

can be the heartless and cunning masters of so many of their

fellowmen, would represent the culmination in that grand ascent

which once happened between the unicellular-being and man.

Fortunately for us all, however, the precious soul- treasures of

by-gone cultures reveal just the opposite. The origin of anything

which is of cultural value will never be found in the struggle-

for-life. Culture has nothing at all in common with strife.

Behold, therefore, how everything which is good in culture

tells a different tale to the materialists. Culture reve'als how

the soul in man awakened when the powers of nature were

threatening to annihilate him and reason was born, which taught

him the life of his own rich soul. Indeed, the final step higher

from mammal to man was more than a mere ascent, for it

'95

taught man to live consciously the Self which was within him,

and enabled him to make the cosmos out of the chaos. Thus a

being had originated which was completely new to whatever

had been, and can resemble therefore the higher species of

animals that suckle their young, only in the form and shape

of the body, and in that the same physiological-laws govern that

body. Just as we might say that volvox, which was the first

mortal many-celled-being resembles still in many ways its one-

celled ancestor. The deeper insight into nature reveals what a

tremendous gulf separates the mammal from man, so that the

arrangement of man among the mammalia as being one and

the same species is certainly a scientific error. By the division

of the species into classes, it should be remembered, in face of

all the physiological likenesses, that a tremendous gulf separates

man from all the other multicellular species; a gulf say, which

is just as sufficient to separate, as the gulf does which divides the

uni-cellular-species from the multicellular species. Now this kind

of arrangement will first bear conviction when our edifice of

thought is being concluded, yet in order to pursue our further

observation with intelligence, we must ask the reader to take

it already as a given fact. We distinguish the classes a little dif-

ferently to the usual scientific habit. They follow thus:

1 Unicell = Protozoan

2 Multicell = Metazoan

3 Man = Hyperzoan.

We know not when or where man was first capacitated to

distinguish his "Self" out of the motley of his surroundings.

Nor when he was aware for the first time that there was a past

and future, so that the force of death was born on him, in that

he saw how plant and animal died, and knew then that death

awaited him also. But one thing we do know, and that is; when

all this was happening, simultaneously there sprang into the

breast of man the longing and hope for Eternity and the pain

196

and tear ot the incomprehensible mixed up with his own tate.

Thus we are justified in saying: in that man succeeded in per-

ceiving the force of death, and that death was in accordance

with nature, the possibility was given to him to become a

hyperzoan.

It comes hard to-day to imagine what the effects were like

which such knowledge must have liberated at that time, because

we were taught in childhood to believe that a conscious life

existed after death, and this at a time when little interest in death

exists a all. Out of the ages, however, in a time when the decept-

ive errors concerning the existence of a heaven were still un-

known, there comes a grand song sounding, which tells of the

overwhelming effects caused by the certainty of death. Patient

stone has preserved the dirge. Among the collection of stone-

tables which once belonged to the Assyrian King Assurbanipal,

there is a cuneiform inscription on one of them. It is the Epos of

Gilgamesh, the man of sorrow and joy. (Translated into German

by George E. Burkhardt, Insel Verlg. Leipzig). First, the life of

the joy-man is described, who was the perfect hero and master

of Uruk, and whose life was filled with heroic deeds which were

inspired by the joyous feelings within his soul. When the death

of his friend Enkidu happened he suddenly changed and became

the man of pain. In his anguish he, "who was like unto a lion",

raised his voice which sounded like the howl of the lioness when

she is struck down with the spear. He tore his hair and strewed

it to the winds; he tore off his garments and put on instead gar-

ments of mourning. Time could neither heal his sorrow nor his

despair. His whole nature was transformed. The unfathomable

mystery of death left him no peace at all. "Shall I also die as

Enkidu has done? My soul is torn with pain, for I have grown

fearful of death. I must hasten over the steppes to the almighty

Utnapischtim, who has found eternal-life. I will raise my head

and voice to Sin the moon, to Nin-Urum who is the Lady of the

197

Castle-of-Life, to the most bright one among the gods. I will

pray thus: "Save my life* 1 . There seems nothing more which

can ever entice him to do heroic deeds; he has become instead

"a wanderer of long ways", for in the ineffaceable sorrow of

his soul, the problem of death concerns him alone. On his terr-

ible journeying he repeats the monotone dirge to everyone he

meets. He is not afraid to pass the dark weird chasms which lead

to "Utnapischtim, the far off one". But here, neither, can the

mystery be solved for him. As we reach the last of the twelve

tables we learn that his wish at last has been granted to him.

The father out of the depths has heard his prayer, and has sent

the shadow of Enkidu to him. Hopes fill our breasts that surely

now poor, despairing Gilgamesh will receive words of comfort

and redemption, for Enkidu will surely describe to him, how

through wonderful liberation into the beyond, he has found

eternal life! But nothing of the kind happens. The grand Epos

concludes in a strain of despair at the terrifying fact that death

is ultimate and inexorable. It concludes with the words, "Each

recognised the other, but remained at a distance". They spoke

to each other. Gilgamesh called and the shadow answered in

quivering tones. Gilgamesh began to speak thus:

* Speak, my friend, speak! Tell me about the laws of the earth

you have seen!"

"I cannot, my friend, I cannot. Did I tell you about the law

ot the earth, I saw, you would sink down and weep."

"Then let me sink down and weep all the days of my life!"

"Behold the friend you once touched, the friend who once

gladdened your heart, the worms are eating, as if he were an

old garment. Enkidu, the friend who once touched your hand

has become earth, has turned to dust. To dust he sank, to dust

he has returned."

Enkidu vanished before Gilgamesh could ask any more quest-

ions.

198

Gilgamesh returned to Uruk, the town with the high walls.

High rises the temple of the holy Mountain.

Gilgamesh lay himself down to rest. Death befalls him in the

glittering halls of his palace.

Here, in stone, fragments have been preserved which relate

the terribly earnest apprehension of death. And a poet of our

century has been priviledged to reconstruct it perfectly for our

benefit! How insignificant the pitiful lot of the semi-conscious

animals that forget the pain quickly which indeed they have felt,

appears now, when compared with the appalling lot of those

unfortunate human-beings who were fated to be the first to

experience the bitterness of death. Their soul-lives were utterly

incapacitated to find balm for their sorrows, for they possessed

neither the strength to bear the thought of life being fleeting nor

the ability to beautify their lives through the knowledge of

death.

Allowing for the difference between man and the mammal to

be but a gradual one, there could still be nothing more shatter-

ing or crushing than the experience of that moment when the

soma-cells of the multicelled individual (man) recognised for

the first time how ultimately they had been robbed of that

immortality which they so deeply yearned for; that, although

they might escape death here and there, it was certain that

they would age one day, decay and return to dust. To be aware

of all this, and to want still to cling to the inner being or the

Immortal-Will is really in itself an impossibility. That long

and grand evolution-process would undoubtedly have ended

in the self-annihilation of the higher animal, called man, had

the spiritual development of man meant truly nothing more

than a better equipment for the struggle-for-life. As it really

is, however, within the course of the thousand years of the hist-

ory of man, very few in comparison have been able to subdue

their Self-Preservation-Will so far as to seek voluntary death.

199

The soma-cells, embued with the Immortal- Will, are con-

tinually concerned, from the very first moment of their lives, in

the industrious occupation of maintaining the cell-state for the

protection of the germ-cells, to be defrauded of immortality

when their work is done, however. Now, where the animals are

concerned, this thought is reconcilable, in as much as their

nonknowledge permits them to labour under the complacent

belief they are serving in the aim of their own self-preservation.

And if we keep before our eyes the lives spent by the higher

animal-species and dwell for a while on their trivial comforts

and short moments of a painless state or actual joy, we must

confess, that, were these even given knowledge of their own

fate, it would still mean the negation of life, not yet the affirm-

ation. This impossibility, which is also an absurdity, is very

noticeable in the state-builders, such as the ants. For the sake

of protection each of these has given up its individual independ-

ance and joined together in a community, building a state as

it were. The struggle-for-life has been made easier. Yet never-

theless, for them, life means nothing else than one continual

burden, which is without the slightest compensation. A chase

towards death, as it were, waylaid with multitudinous troubles.

Now were these to possess the slightest knowledge of their own

fate, it would mean the sure annihilation of life itself, as there

would be no want to live as a consequence.

Man, however, has remained the affirmer of life he is, inspite

of his knowledge of death. And the basis of this affirmation of

life does not rest on the fact that it is a physiological impossi-

bility for man to overcome his self preservation-will, for volunt-

ary deaths do (although seldom) occur, giving evidence of this.

Thus then, the step from mammal into achieved man must have

brought a benefit with it other than a mere better equipment

for the struggle-for-life, a benefit indeed, in so much, as it served

to counter-balance his transitory lot, or effaced the conflict in

200

his soul completely. There is still another possible alternative.

If there could be found no counter-balance at all nor anything

which was adequate to appease the conflict raging within his

soul, nevertheless there crept within his soul a feeling, very

vague no doubt, which inspite of his knowledge of death and all

the tribulations he seemed bound to suffer, was able to sustain

him. It whispered to him thus: There is something indeed, which

I too am capable of attaining.

But after all is said, does the inevitable fate of death (which

awaits all men) really make the world men live in so diconsolate?

Do not the majority of us face this fact in a blind attitude and

absolutely unenquiringly? When we think of Gilgamesh, who

because he loved his friend so well, was made to stagger before

the stern fact of death, afterwards experiencing neither joy not

peace but dedicated his whole life to the solving of its mystery,

we can hardly span the gulf at all which lies between such

divergent attitudes. Well now, the hero of the legend belongs

to those rare kind of men, who dedicate their thoughts to the

ultimate things of life as soon as they are caught in the webs of

their mysteries. Such deep longings and ponderings are beyond

the spiritual powers of the ordinary indifferent individual. It

seems a tremendous pity that such rare sensitive souls, like

Gilgamesh was made of, could not have been spared, at so

primitive a stage of intelligence, the knowledge that death was

inevitable. It was the consciousness of Self and the conscious

application of that 'aprioristical* feeling of time, space and

causality which awakened in that time of dangerous combat

against the cosmical powers, which led to the sure knowledge

of death. This occured at a very primitive stage when com-

prehension of the laws of the universe was not far above the

level of the higher animal species. But something more was

required as we shall see in the course of the following, to cope

adequately with the conflict between immortality and natural

201

death. This was an exalted state of cultural development, to-

gether with a high degree of world-knowledge which could be

obtained through the powers of reason only. A few suspected

it and sensed it, although these factors were of little aid leading

to clarity, so that thousands of years were doomed to pass and

were wasted in futile attempts to solve this mysterious apparent

absurdity. As a consequence of all these false attempts, appeared

the deviation and return to paths and ways that were only

partially right, and the change from flourish to decline of once

promising cultures. Like the butterfly will burn its wings and

die when it flies into the light, non-cognisant of its harmful

nature, the cultures of by-gone ages also have fallen to ground

with burnt wings, because they flew into the glaring light of

knowledge. If any were saved, it was not due to the correctness

of their flight in the drive for truth, but because of their stolidity

which kept them creeping animal-like upon the ground; to have

the priviledge afterwards, however, of being upheld as the

superior ones in life.

And yet, inspite of all the paths of error and deviation from

truth over which the mind of man wandered in his grave at-

tempts to overcome the conflict between his Will-to-Immortality

and the fact that natural death awaited him, we can easily

perceive how the soul of man from times immemorable seemed

to feel so rightly of its own accord where redemption really

lay although the feeling itself was so faint and feeble. It finds

expression in almost all the myths of the primitive folks, and

more especially in the different kinds of religions professed by

the so-called cultural folks; in a manner so adequate that one

might be tempted to believe the myths alone would have

sufficed to have directed mankind towards the right way to

redemption. But alas! we were obliged to witness how this right

feeling went astray through the very gift of knowledge, or let

us say rather through "false knowledge" (which became ob-

202

tainable through the powers of reason). For, the explanations

and arguments which reason was forever apt to bring forth,

together with its fatal habit of conducting the laws-of-causality,

time and space to realms which lay beyond this form of intellect,

were a grave misapplication, which of a necessity led, not only

the believers but also the very creators of the myths themselves

astray! Thus then, through the destructive work of intellectual-

reasoning, all the beneficial effects which the images of art and

the religions aimed at, became futile. After a period of cultural

flourishment, or flight towards liberation, a race would sink

to earth with burnt wings, at the best to give place to another

which would but repeat the attempt and decline in the same

way.

The critical point for them all arrived at that time, when

reason having reached a state of half-knowledge and refusing

to be fooled and mortified by the mode of thought offered in

the myths, became bold enough to decry altogether the Immor-

tal-Will and the Divine, ridiculing the affirmation of these as

being sheer nonsense! The crisis in the disease of the cultures

was marked through the disdain mankind showed for the wis-

dom of the poets because of the obvious errors (always inter-

woven with the truth), which they perceived. As a consequence

these were totally ignored and the once honoured gods forsaken,

and there being nothing else ready to substitute the old faith,

the emptiness which had been left behind in the soul of man

remained. The 'man of culture' then, at such times, owing to

the silliness of his reason's half-knowledge, was less capable of

coping with the spiritual state in which he found himself to be,

where his Immortal- Will was in constant conflict with natural

death, than ever his predecessors were who still believed in the

myths. In fact he was even more helpless than his very ancient

predecessor, Gilgamesh, who had no myth at all to give him

spiritual strength, but who, inspite of this, instinctively felt

203

that to understand he meaning of death signified the solution of

the soul's mystery.

Before we concern ourselves further with all the erroneous

paths once trodden by those unique human souls whose habit

it became, in their eager search for liberation, to ponder over

the ultimate matters as being the main ones in life, let us stop

for one moment to visualise all the consolations man created

for himself. We must first clearly understand, and our powers

of discrimination will be of help to us in doing so, that the

Immortal-Will, in reality, has nothing to do with the longing

in the soul for happiness, a fact which natural science has par-

ticularly clearly given utterance to, in having termed this the

"self preservation instinct". This aims at living on without any

interuption, or final end. It simply wants to exist, independent

of any accompanying emotions of pleasure or pain. Hence it

happens that the animal is driven to bear unswearingly the

miseries of its joyless life like the man who enjoys the full of

his life. The fact that the Immortal-Will was non-identical with

the will for pleasure or "Happiness" (that is the desire to realise

as often as possible the strongest possible pleasurable sensations)

explains the reason why the average individual could, and still

can find, in happiness, the full compensation for immortality,

and in a mad chase after happiness apparently overcomes the

conflict. Moreover, as the soul of man was endowed, not only

with a higher state of consciousness but also with the gift of

reason, an ability was likewise given him to escape that unfa-

vourable state of mind of the higher mammal-species, which

suffers long periods of pain and enjoys, relatively speaking,

very short spans of pleasurable sensations. It was reason which

aided man in sparing him from suffering periods of alternate

famine and abundance. He divided his quantities of food-stuffs,

so that, actually speaking, the majority have never once ex-

perienced what hunger means. Man was not compelled even

204

to stop at this. It lay in his power to give manifold change to

his food. He did so, considering his own personal taste with

such devotional care as to make food become a veritable fount

of the greatest of all pleasures, meaning happiness its very self.

He felt indeed fully compensated for the transitoriness of his

own life. There is still another sensation of pleasure existing

which has the prerogative of rendering greater recompense.

Before reason awakened it became essential, as we have already

seen, that a certain pleasurable sensation should be accelerated,

in order to find its satisfaction in the function of reproduction,

thus assuring its fulfillment; and as the vertibrates for the better

protection of the coming generation took to the inner fructificat-

ion a bodily-sexual-intercourse became necessary. And although

within the course of evolution, through the gradual association of

the pairing- will and the soul-life, tremendous spiritual benefits

were gained, the majority of mankind are still incapacitated to

emancipate above the dull form akin to the animal when indulg-

ing in sexual-happiness. And yet, this primitive form was in

itself sufficient to mean 'life's happiness*. Contrary to the ani-

mal, man's intellect aided and abetted him in the invention of

all manner of ways and means to repeat at will his sexual

sensations of pleasure. (We shall come back to this later.) Hence,

there is every justification to say that the sensations of sexual-

pleasure signifies the greatest recompense to the majority of

mankind.

These "delights" (beautifying existence) were not the only

results, however, which the ascent from mammal to man be-

queathed to mankind. Man is often tempted to consider aging,

decaying and final death more in the light of a blessing than

otherwise as it puts an end to the many tribulations of man on

earth (spared fortunately to the animal-kingdom). For instance,

the increase in population, effected through man's inventive

powers in gaining means to protect him from danger in emerg-

205

ency, gradually accelerated to over-population making the

struggle-for-existence for the majority almost unbearable. Many

were subjected to others greedy of power and gold, which caused

their lives to become a state of veritable misery. By its very law,

the keen sensitiveness of man's own soul has been also the means

of much of the pain and misery in the world, so that Schiller

was justified when he made the utterance. "Everywhere the

world is perfect, where man with his pain is not." This subject,

incidently, is of such profundity, that it has a right to be treated

very minutely. We can mention here, in short, where the roots

of the evil lie. The greatest fault lies with memory above

everything else, inspite of its apparent harmlessness. Unlike

the animal-memory, by the very virtue of its keenness, it is

incapacitited to forget either any suffering or hate towards an

enemy. The higher animal-species forget as soon as danger has

passed. According to our observation, the average individual,

(as the fruits of his higher consciousness) is able to pile up his

pleasure, considering them to be the sole worthy contents of

his life. Of a necessity must this also bring a second appalling

effect with it. Man is not only capacitated to understand and

keep in his memory his own sufferings. He can extend these to

the pleasures of others. In this way "Envy" arises, poisoning

his surroundings. And verily the life of most people consists

in a continual hoarding up of their own-made miseries, so that

the creed which documents that the earth is 'a vale of tears'

has apparently found its justification at all times. Besides the

consolations of indulging freely in the bodily sensations of

pleasure, a second one appeared in opposition. Natural death

or the certainty of the transitoriness of life became something

worth looking forward to; it was taught in fact to be a consol-

ation and reconciling certainty which gave man the strength

to bear life's tribulations. Not only do all those who are per-

secuted with pain follow this sheer negative form of consolation,

206

but also, (curiously enough) all those others called the "Hedo-

nist", who consider the aim and affirmation of life to be in the

massing up of as much pleasure before old age and illness steps

in to be a hinderance. In the end it can induce man to ignore

his Immortal- Will as being but an idle desire. It can drive

poor weak-willed creatures even to commit suicide.

Such meagre consolation can hardly be considered as a fit

recompense for the Immortal-Will, no matter how apt reason

was to become reconciled to the idea in certain conditions of life.

The feeling of the soul itself, when it awakened that time to

consciousness, was a better consolation. Decrying bravely all

reason's wisdom, it relied solely on the mneme inherited from

the unicell, which told of the surety of immortality. And al-

though the fact of inevitable death could not be contradicted, it

denied that death was death in the real sense of the word. It

proclaimed that only the visible or the outward appearance

died, but not the invisible or soul (the "Thing Itself") which

animated the outward appearance. One curious fact, however,

is, that the myths contained in most of the religions, account

immortality to man alone among all the rest of the visible world,

inspite of the fact that reason had had evidence enough that man

as much as the animals was subject to the laws of death in as

much as all his cells, (like those of the animal) after a process of

gradual burning, which is called decay, become again the simpl-

est of organic matter. This conception could not be shattered.

The invisible, albeit animate in man, contrary to that in the

animal, had part in the beyond! Later on, we shall see how true

that presumptive feeling was which said the animals were un-

redeemable!

And so alarmed, apparently, was the Immortal- Will over the

fact that death was obligatory, that it created for itself (in the

myths) a perpeptual conscious life; an idea to reason quite

appalling. And so it came about that in the myths the actual

207

world was represented as an illusionary world, a vale of tears,

which could prove of great impediment to eternal bliss but which

unfortunately we had to pass through if we wanted to gain our

eternal home. Now, the vigorous will-to-live, deeply mortified

at the fact of death, started to decorate the beyond with every-

thing that seemed worth living for. (How touching for example,

are all those visions of a beyond which the 'primitive peoples'

have imagined for themselves.) As reason compelled both anticip-

ation and myth to build their beyond in the spheres of space,

the Immortal- Will one day, was bound to perceive its heavens

laid in ruins, as a consequence of the progress of intellectual

knowledge. It was, furthermore, forbidden to exist even beyond

the clouds. It was roughly brushed aside after Copernicus had

indicated the spheres where stars in systems circle. And even

still undaunted, the Immortal-Will was able to reconstruct out

of the ruins another mythical heaven. This time it lay even

beyond the universe 'whose unendlessness of space was of no

significance to the soul delivered of its body*.

And once again, as result of our study, reason has shattered

the mythical heaven, this time in its very foundations, for our

reasoning-powers have accomplished facts which are of a deeper

significance than a mere spherical disarrangement of the firma-

ment. The powers of intellect, having been priviledged so far

as to be able to penetrate into the coherency of the evolution

history, have as a consequence, been also able for the very first

time, to point out the fact that the Immortal- Will must essent-

ially be innate in the mortal soma-cells too, for were it not

so, these would hardly have let themselves be called upon to

sacrifice themselves so entirely for the sake of the eternal germ-

cells. On the other hand, there is also sufficient evidence, that

all the different kinds of the soma-cells (or body-cells), including

of -course the brain-cells belonging to the multi-celled individual

(man included) have no part in the immortality of the germ-

208

cells. The history of evolution furnishes ample witness why

and how it happened that a transitory individual, such as man

is, without possessing the characteristic of immortality, could

yet be so sternly conscious of the fact of his own immortality.

It was owing to these facts, that the history of evolution under-

mined most cruelly the foundations upon which the heavens

of the past were built; those foundations which had even defied

reason so long, the argument being: "If a human-being be really

doomed to pass away for ever, how could the strong desire and

certainty of eternity which certainly exists within him be ac-

counted for?"

Now, if truly mneme, or the sub-conscious memory, which

of a necessity, in the progress of evolution permitted the soma-

cells to retain their Immortal-Will, inspite of inevitable death,

was alone responsible for the certainty of immortality here

manifested, then indeed one could be obliged to say that reason

had gained the victory over the myth of immortality. And man

would have nothing left to do than habituate himself to the

fact of inevitable death. As it is, however, in sharp contradiction

to Darwinism, one thing remains certain, and that is; while

guarding ourselves implicitly against the error which reason

makes when it forms actual conceptions of god as being a person

there is every evidence for believing in that invisible, unfathom-

able, nature lying in all things, which of-course can only

be felt or experienced and is generally known by the name

of God, the "Thing Itself", the Divine or Genius etc.; a

belief too which moreover can bear the full light of the history

of evolution without its being shattered to pieces. Here there

can be found no negation of the Divine, on the contrary, it is

verified in such a grand manner as never before. We have already

been priviledged to recognise that all the explanations in the

light of the mere mechanical only which have been put forth

in regard to the history-of -evolution are errors. Instead, abund-

209

ance of evidence is always proving that a will, animated with

a distinct aim in view, at every significant stage in the ascent

of man, enforced form for itself in every living thing, albeit this,

itself was utterly unconscious of the fact. Hence, the history-

of-evolution has benefitted us in a wonderful way, for we are

no more called upon to say, "I believe in God" but "I know

that every animate and inanimate being belonging to the uni-

verse, is the visible appearance of the invisible-Divinity existing

within it, and that this innate godlikeness of the mortal body-

cells enforced its own manifestation in the appearance of the

manifold forms and shapes unique to the different multi-celled

beings, a process, moreover, which signified the wish to ascend

from the deepest kind of unconsciousness to the highest form

of consciousness in man."

Faith in immortality can also deepen into knowledge of

immortality. After the intuition I had experienced of the truth

of the immortality of man, I was easily facilitated to complete

the edifice of my thought, placing facts so neatly together that

it appeared afterwards as if it had fructuated from intellectual

thought and not from an intuitive source. Now, when intuition

rings true, reason subsequently is able to build up the steps which

leads to it. But at a time as this, when reason is so tremendously

overrated, and the soul-awareness (Erleben) of truth not enough

appreciated, it would be a great injustice were the following fact

not stressed, which is, that the powers of reasoning in this case

were very limited, in as much as they were most certainly

capable of indicating rightly the way to the wisdom we expound,

but, on the other hand, absolutely incapable of solving the con-

flicting mystery existing between natural death and reason

itself. First, a time of deep contemplation into the myths of the

different folks, and also a deep contemplation of the soul were

necessary, before light could be thrown into the sequence of

matters. So let us now ponder this time together to make sure

of the fact that a sufficient study of the myths, when unin-

fluenced by Darwinian thought, will lead finally, not to their

rejection, but to a high appreciation of them, albeit their con-

tents be as full of errors as of truths.

Among all the various fantastical religious poems which

belong to the different folks of the earth, there are four different

major kinds of myths which occur over and over again. Of

these, two are concerned with the past and two with the future

fate of the soul.

The myth of the history of creation relates how, through the

will of a higher invisible being, all the manifold creatures seen

on earth originated at a period of the earth's history in quick

succession, and that man, among all the other beings stood in a

special relationship to this invisible being, a being "of the

spirit of Brahman, the most pervaded one". Furthermore, that a

like creation-process never again will occur; the Indian myth

goes even so far as to tell of the affinity and uniformity of all

the visible-scene. The observation which we have made ourselves

of the history of evolution, compells us to confirm the truth

this myth contains, in as much as we strictly avoided viewing

it in the narrov Darwinian outlook, and concerned ourselves

with just the essential part, discarding deliberately all the fan-

tastical images and those contents which were concerned with

a personification of the Divine.

The second myth concerned with the past is the fantastical

description of a "Paradise-Lost". Here the poets sing of a time

when the earth knew of no aging, decaying nor death; a time,

in fact, in which men lived in eternal youth without sufferings

of pain or desire. This the doctrine of evolution confirms to be

true also, for, indeed, there lived in the hearts of the poets a

faint remembrance of the potential immortality of our one-celled

predecessors that felt neither pain nor desire, and knew nothing

of 'age* nor death.

211

14+

Then there are two myths which are very deeply concerned

with the future of man and the destiny of his soul. A belief,

peculiar to the Germanic race, and of which strong traces can

be found in the religious conceptions in the ancient Indian

Vedas, is the faith in reincarnation. In the Edda, an echo of it is

still to be found, clothed in language of great poetical beauty!*

Here we are made aquainted with the hero, called Helge, who,

as a single exception, was once given back to life. The song,

however, concludes with the firm belief in the reincarnation

of the ancestors. Helge and Siegrun are born again as Helge

Haddingenheld and Kara. The Vedas cling still even more

lovingly to this myth, and it is varied in every way. These

recount the stories of the soul's reincarnation, how it appears

on earth fettered first in animal nature, and how afterwards,

at every new birth it takes on a more god-like form. The

doctrine of reincarnation is truth likewise, in as much as it is

identical with the "mneme", or true remembrance, which is

revealed in the process of evolution and is the fate which the

soul has actually passed through. This must have been a very

faint remembrance, much fainter than the remembrance, of

the "paradise lost", which is the life once experienced by all

the protozoa, so that the remembering animate-being, although

it is a descendant of discrepant germ-cells has inherited from

the ancestral cells the remembrance of the once universal prime

and immortal ancestor as well. The remembrance characteristic

of the once experienced life of any animal or man may not

simply be attributed to the brain cells and left at that, for the

germ-cells from which the remembering brain-cells descend, are

not the descendents of single individuals only, but of a multi-

tude, which all bear promiscuous heritage. New synthetic hypo-

theses are not essential to support this as being a scientific fact,

as this kind of memory springs likewise into existence in exactly

* Gorsleben Edda P. 41. Publishers Heimkehr Verlag Miinchen-Pasing.

212

the same way as the "mneme" does in the case of the inherited

instinct which belongs to the animals, which everywhere is

accepted by science. (Nest-building instinct of the birds). Since

this means, as regards to the single individual, that the inherited

substance of the germ-cells is of a necessity associated with the

brain-cells, it also means that it is also associated with the soul

of the bird which is nest-building. It was only along these lines

that it was made possible for the capacity of nest-building to

be bequeathed to succeeding generations at that time when it

was being done for the first time by one of its kind. Now, our

own souls are no unpromiscuous descendants of single individ-

uals, and owing to this we are liable at times to have visions

or feel as if we had experienced certain conditions in a former

life already. They are of a mere fleeting and passing kind for

the reason that our own souls have no affinity whatever with

the ancestral-being. Within us we contain, so to speak, innu-

merable bits of memory of the experiences which once belonged

to each one of our ancestors, and which has been transmitted

to us in a promiscuous collection. It was the force of these

facts which made it impossible, at all times, to give up the

belief in one's own immortality and replace it with the belief

in the immortality of the kind. It is a thing impossible to trans-

mit our own personality unadulterated to succeeding generations;

at the very best, only a few characteristics can be transmitted,

but even these are liable to be mixed with other traits which

are wholly alien to our nature. So that, seen from a scientific

view, the belief in the reincarnation cannot find any support

through the fact of the "mneme", nor could it bear so much

conviction as the belief in the other myths did, as for instance

the myth of a lost paradise, or as it is called in the Edda*

*I refer the reader here to my work f entitled^ "Eadi Folk's ^own r Song to

erei

ing

cipatu

* 1 refer the reader nere to my wprx enmiea: cam rom s own oong 10 vjoa

wherein I have attempted to point out in chapter "The Religions Fall from their God-

living Heights" how bad-reasoning and misconceptions has helped to distort this anti-

cipation once described in the myth making antigodlike error out of it.

"Midgard" where the state of immortality was granted to our

ancestors.

The last of the four myths is the best known and is considered

in general as the most significant and is revered accordingly.

This myth is concerned wholly with the immortal state, or

belief in an eternal-life (after death). Now, if nothing else than

the strong feelings of nostalgia and assurance of immortality

were expressed we should have no cause to take increased

thought in this matter, as we have seen that the process of

evolution gave sufficient foundation for them. What made us

stop to ponder more deeply, is the fact we encounter every-

where, and which we have already hinted; the exclusion of the

animals from partaking in a life hereafter, for, according to

our faith in the process of evolution, in which sense the "Mneme"

confirms strongly the uniformity of man and animal-fate, the

reverse could be expected. And further, curious though it sounds,

we encounter the repeated assurance that heaven is not for